- Wolfhunting in Russia

The enormous extent and diversified conditions of the various localities of this empire would naturally suggest a variety of sport in hunting and shooting, including perhaps something characteristic. In the use of dogs of the chase especially is this suggestion borne out by the facts, and it has been said that in no other country has the systematic working together of fox-hounds and greyhounds been successfully carried out. Unfortunately, this sort of hunting is not now so general due to the emancipation of the serfs in 1861. A modest kennel for such sport consists of six to ten fox-hounds and four to six pairs of barzois,* and naturally demands considerable attention. Moreover, to use it requires the presence of at least one man with the fox-hounds and one man for each pair or each three greyhounds.

To have a sufficient number of good huntsmen at his service was *Barzoi—long-haired greyhound, wolf-hound, Russian greyhound. a much less expensive luxury to a proprietor than now, and to this fact is due the decline of the combined kennel in Russia. This hunt is more or less practised throughout the entire extent of the Russian Empire. In the south, where the soil is not boggy, it is far better sport than in Northern Russia, where there are such enormous stretches of marshy woods and tundra. Curiously enough, nearly all the game of these northern latitudes, including moose, wolves, hares, and nearly all kinds of grouse and other birds, seem to be found in the marshiest places—those almost impracticable to mounted hunters.

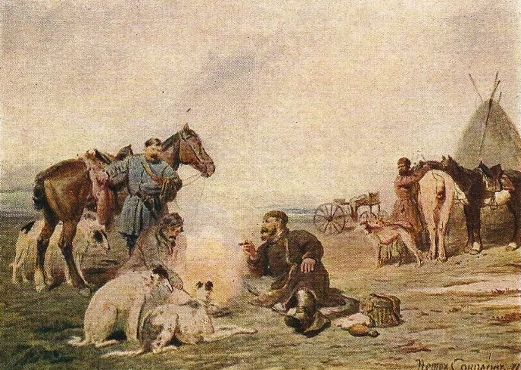

Though the distances covered in hunting, and also in making neighborly visits in Russia, are vast, often recalling our own broad Western life, yet in few other respects are any similarities to be traced. This is especially true of Russia north of the Moscow parallel ; for in the south the steppes have much in common with the prairies, though more extensive, and the semi-nomadic Cossacks, in their mounted peregrinations and in their pastoral life, have many traits in common with real Americans. Nor is it true of the Caucasus, where it would seem that the Creator, dissatisfied with the excess of the great plain,* extending from the Finnish Gulf to the Black Sea, resolved to establish a counterpoise, and so heaved up the gigantic Caucasus.

There, too, are to be found fine hunting and shooting which merit description and which offer good sport to mountain amateurs. The annual hunt in the fall of 1893 in the governments of Tver and Yaroslav, with the Gatchino kennels, will give a good idea of the special sport of which I have spoken. It is imperative that these hounds go to the hunt once a year for about a month, although for the most part without their owner. The master of the hunt and his assistant, with three or four guests and oftentimes the proprietors of the lands where the hounds happen to hunt, usually constitute the party. The hunt changes locality nearly every year, but rarely does it go further from home than on this occasion, about 450 versts from Gatchino. As a rule it is not difficult to obtain from proprietors permission to hunt upon their estates, and this is somewhat surprising to one who has seen the freedom with which the fences are torn down and left unrepaired.

* The Waldeir hills, extending east and west half-way between St.Petersburg and Moscow, are the only exception.

It is true that they are not of the strongest and best type, and that peasant labor is still very cheap ; yet such concessions to sport would rarely be made in America. It was at Gatchino, on the l0th day of September, that the hunting train was loaded with men, horses, dogs, provisions and wagons. The hunt called for twenty-two cars in all, including one second-class passenger car, in one end of which four of us made ourselves comfortable, while in the other end servants found places. The weather was cold and rainy, and, as our train traveled as a freight, we had two nights before us. It was truly a picturesque and rare sight to see a train of twenty-two cars loaded with the personnel, material and live stock of a huge kennel.

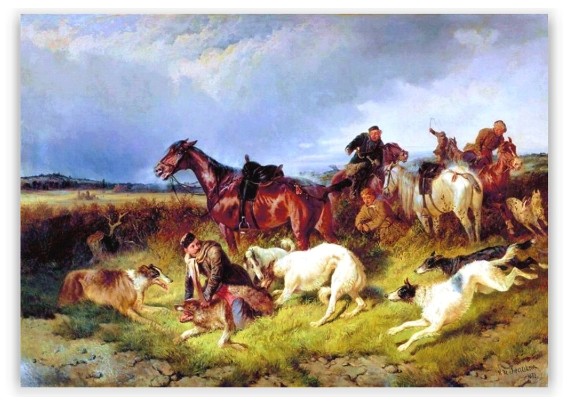

The fox-hounds, seventy in number, were driven down in perfect, close order by the beaters to the cracks of the Russian hunting whip and installed in their car, which barely offered them sufficient accommodation. The greyhounds, three sorts, sixty-seven in number, were brought down on leashes by threes, fours or fives, and loaded in two cars. Sixty saddle and draft horses, with saddles, wagons and hunting paraphernalia, were also loaded. Finally the forty-four gray and green uniformed huntsmen, beaters, drivers and ourselves were ready, and the motley train moved away amid the uttered and unuttered benedictions of the families and relatives of the parting hunt.

Our first destination was Peschalkino, in the government of Tver, near the River Leet, a tributary of the Volga, not far from the site of the first considerable check of the Mongolian advance about 1230. I mention this fact in passing to give some idea of the terrain, because I think that it is evident to anyone who has visited this region that the difficulty of provisioning and of transportation in these marshes must have offered a greater obstacle to an invading army than did the then defenders of their country. We passed our time most agreeably in playing vint* and talking of hunting incidents along the route. Many interesting things were told about the habits of wolves and other game, and, as they were vouched for by two thorough gentlemen and superb sportsmen, and were verified as far as a month’s experience in the field would permit, I feel authorized to cite them as facts.

* Vint—game of cards resembling whist.

The bear has been called in folklore the moujik’s brother, and it must be conceded that there are outward points of resemblance, especially when each is clad in winter attire; moreover the moujik, when all is snow and ice, fast approximates the hibernating qualities of the bear. One strong point of difference is the accentuated segregative character of the former, who always live in long cabin villages.*

But it is rather of the wolf’s habits and domestic economy that I wish to speak—of him who has always been the dreaded and accursed enemy of the Russian peasant. In the question of government the wolf follows very closely the system of the country, which is pre-eminently patriarchal—the fundamental principle of the mir. A family of wolves may vary in number from six to twenty, and contain two to four generations, usually two or three, yet there is always one chief and one wife—in other words, never more than one female with young ones.

* The bear is caricatured in Russian publications as a humorous, light-hearted, joking creature, conversing and making common ith the golden-hearted moujik, his so-called brother.

When larger packs have been seen together it was probably the temporary marshaling of their forces for some desperate raid or the preliminaries of an anarchistic strike. The choruses of wolves and the special training of the young for them are interesting characteristics. Upon these choruses depends the decision of the hunter whether or not to make his final attack upon the stronghold of the wolves; by them he can tell with great precision the number in the family and the ages of the different members.

They are to wolf-hunters what tracks are to moose- and bear-hunters—they serve to locate the game. When the family is at home they occur with great regularity at twilight, midnight and dawn. In camp near Billings, Montana, in the fall of 1882, we heard nightly about 12 o’clock the howling of a small pack of coyotes; but we supposed that it was simply a “howling protest” against the railway train, passing our camp at midnight, that had just reached that part of the world. Possibly our coyotes have also howling choruses at regular intervals, like the Russian wolves.

There was such a fascination in listening to the wolves that we went out several times solely for that purpose. The weirdness of the sound and the desolateness of the surroundings produced peculiar sensations upon the listener. that the wolves were “at home” at midnight as well as dawn. While in the vicinity of a certain wolf family whose habitat was an enormous marshy wood, entirely impossible to mounted men, we were compelled to await for forty-eight hours the return of the old ones, father and mother. At times during this wait only the young ones, at other times the young and the intermediate ones, would sing. Not hearing the old ones, we inferred they were absent, and so they were off on a raid, during which they killed two peasant horses ten miles from their stronghold. It was supposed that the wolves of intermediate age also made excursions during this time, as indicated by the bowlings, but not to such great distances as the old ones. It was perfectly apparent, as we listened one evening, that the old ones had placed the young ones about a verst away and were making them answer independently. This seemed too human for wolves.

After one day and two nights of travel we arrived at the little station of Peschalkino, on the Bologoe-Rybinsk Railway, not far from the frontier between the two governments, Tver and Yaroslav, where we were met by two officers of the guard, a Yellow Cuirassier and a Preobiajensky, on leave of absence on their estates (Koy), sixteen versts from the rail. They were brothers-in-law and keen sportsmen, who became members of our party and who indicated the best localities for game.on their property, as well as on the adjoining estates. Peschalkino boasts a painted country tavern of two stories, the upper of which, with side entrance, we occupied, using our own beds and bed linen, table and table linen, cooking and kitchen utensils; in fact, it was a hotel where we engaged the walled-in space and the brick cooking stove. As to the huntsmen and the dogs, they were quartered in the adjacent unpainted log-house peasant village —just such villages as are seen all over Russia, in which a mud road, with plenty of mud, comprises all there is of streets and avenues.

After having arranged our temporary domicile, and having carefully examined horses and dogs to see how they had endured the journey, we made ready to accept a dinner invitation at the country place of our new members. Horses were put to the brake, called by the Russians Amerikanka (American), and we set out for a drive of sixteen versts over a mud road to enjoy the well-known Slav hospitality so deeply engrafted in the Ponamaroff family. I said road, but in reality it scarcely merits the name, as it is neither fenced nor limited in width other than by the sweet will of the eler. Special mention is made of this road because its counterparts exist all over the empire. It is the usual road, and not the exception, which is worse, as many persons have ample reasons for knowing. This condition is easily explained by the scarcity of stone, the inherent disregard of comfort, the poverty of the peasants, the absence of a yeoman class, and the great expense that would be entailed upon the landed proprietors, who live at enormous distances from each other. The country in these and many other governments has been civilized many generations, but so unfinished and primitive does it all seem that it recalls many localities of our West, where civilization appeared but yesterday, and where tomorrow it will be well in advance of these provinces. The hand-flail, the wooden plowshare, the log cabin with stable under the same roof, could have been seen here in the twelfth century as they are at present. Thanks to the Moscow factories, the gala attire of the peasant of today may possibly surpass in brilliancy of color that of his remote ancestry, which was clad entirely from the home loom. With the exception of the white brick churches, whose tall green and white spires in the distance appear at intervals of eight to ten versts, and of occasional painted window casings, there is nothing to indicate that the colorings of time and nature are not preferable to those of art. The predominating features of the landscape are the windmills and the evenness of the grain-producing country, dotted here and there by clumps of woods, called islands. The churches, too, are conspicuous by their number, site, and beauty of architecture; school-houses, by their absence. Prior to 1861 there must have been a veritable mania here for church-building. The land, and beautiful church at Koy, as well as two other pretentious brick ones, were constructed on his estates by the grandfather of our host. Arriving at Koy, we found a splendid country place, with brick buildings, beautiful gardens, several hot-houses and other luxuries, all of which appeared the more impressive by contrast. The reception and hospitality accorded us at Koy—where we were highly entertained with singing, dancing and cards until midnight —was as bounteous as the darkness and rainfall which awaited us on the sixteen versts’ drive over roadless roads back to our quarter bivouac at Peschalkino.

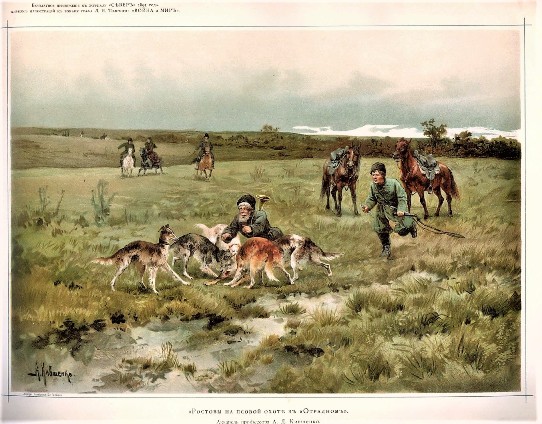

The following morning marked the beginning of our hunting. About 10 o’clock all was in readiness. Every hunter* had been provided with a leash, a knife and a whip; and, naturally, every huntsman with the two latter. In order to increase the number of posts, some of the huntsmen were also charged with leashes of greyhounds. I shall in the future use the word greyhound to describe all the sight hounds, in contradistinction to foxhound ; it includes barzois (Russian greyhounds), greyhounds (English) and crosses between the two. The barzois numbered about 75 per cent. of all the greyhounds, and were for the most part somewhat less speedy than the real greyhounds, but better adapted for wolf-hunting. They also have greater skill in taking hold, and this, even in hare coursing, sometimes gives them advantage over faster dogs. One of the most interesting features of the coursing was the matching of Russian and English greyhounds. The leash system used in the field offers practically the same fairness as is shown by dogs at regular coursing matches. The leash is a black row leather thong about fifteen feet long, with a loop at one end that passes over the right shoulder and under the left arm. The long thong with a slit at the end, forming the hand loop, is, when not in use, folded up like a lariat or a driving rein, and is stuck under the knife belt. To use it, the end is put through the loop-ring collars, which the greyhounds continually wear, and is then held fast in the left hand until ready to slip the hounds. Where the country is at all brushy, three dogs are the practical limit of one leash, still for the most part only two are employed. It is surprising to see how quickly the dogs learn the leash with mounted huntsmen two or three days are sufficient to teach them to remain at the side of the horse and at a safe distance from his feet. Upon seeing this use of the leash with two dogs each, I was curious to know why it should be so; why it would not be more exciting to see half a dozen or more hounds in hot pursuit racing against each other and having a common goal, just as it is more exciting to see a horse race with a numerous entry than merely with two competitors. This could have been remedied, so I thought, by having horsemen go in pairs,or having several dogs when possible on one leash. Practice showed the wisdom of the methods actually employed. In the first place, it is fairer for the game; in the second, it saves the dogs ; and finally, it allows a greater territory to be hunted over with the same number of dogs.

There are two ways of hunting foxes and hares, and, with certain variations, wolves also. These are by beating and driving with foxhounds, and by open driving with greyhounds alone. In the first case a particular wood (island) is selected, and the fox-hounds with their mounted huntsmen are sent to drive it in a certain direction. The various leashes of greyhounds (barzois alone if wolves be expected) are posted on the opposite side, at the edge of the wood or in the field, and are loosed the second the game has shown its intention of clearing the open space expressly selected for the leash. The mounted beaters with the fox-hounds approach the thick woods of evergreens, cottonwood, birch and undergrowth, and wait on its outskirts until a bugle signal informs them that all the greyhound posts are ready. The fox-hounds recognize the signal, and would start immediately were they not terrorized by the black nagazka—a product of a. country that has from remotest times preferred the knout* to the gallows, and so is skilled in its manufacture and use. At the word go from the chief beater the seventy fox-hounds, which have been huddled up as closely as the encircling beaters could make them, rush into the woods. In a few minutes, sometimes seconds, the music begins—and what music! I really think there are too many musicians, for the voices not being classified, there is no individuality, but simply a prolonged hovel. For my part, I prefer fewer hounds, where the individual voices may be distinguished. It seemed to be a needless use of so many good dogs, for half the number would drive as well but they were out for exercise and training, and they must have it. Subsequently the pack was divided into two, but this was not necessitated by fatigue of the hounds, for we hunted on alternate days with greyhounds alone.

One could well believe that foxes might remain a long time in the woods, even when pursued by such noise; but it seemed to me that the hares. would have passed the line of posts more quickly than they did. At the suitable moment, when the game was seen, the nearest leash was slipped, and when they seemed to be on the point of losing another and sometimes a third was slipped. The poor fox-hounds were not allowed to leave the woods; the moment any game appeared in the open space they were driven back by the stiff riders with their cruel whips. The true foxhound blood showed itself, and to succeed in beating some of them off the trail, especially the young ones, required most rigorous action on the part of all. This seemed to me a prostitution of the good qualities of a race carefully bred for centuries, and, while realizing the necessity of the practice for that variety of hunt, I could never look upon it with complaisance.

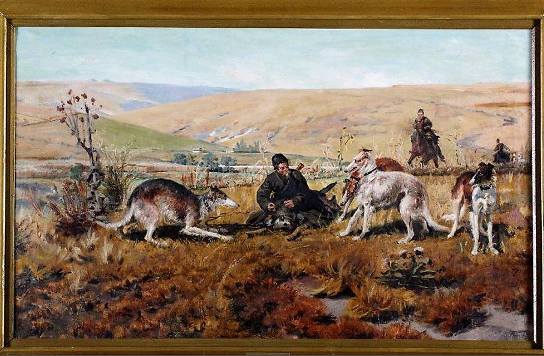

It is just this sort of hunt* for which the barzoi has been specially bred, and which has developed in him a tremendous spring; at the same time it has given him less endurance than the English greyhound. It was highly interesting to follow the hounds with the beaters; but, owing to the thickness of the woods and the absence of trails, it was far from being an easy task either for horse or rider. To remain at a post with a leash of hounds was hardly active or exciting enough for me–except when driving wolves—especially when the hounds could be followed, or when the open hunt could be enjoyed. In the second case the hunters and huntsmen with leashes form a line with intervals of many yards and march for versts straight across the country, cracking the terrible nagaika and uttering peculiar exciting yells that would start game on a parade ground. After a few days I flattered myself that I could manage my leash fairly and slip them passably well. To two or three of the party leashes were not intrusted, either because they did not desire them or for their want of experience in general with dogs and horses. To handle a leash well requires experience and considerable care. To prevent tangling in the horse’s legs, especially at the moment the game is sighted, requires that the hounds be held well in hand, and that they be not slipped until both have sighted the game. I much prefer the open hunt to the post system. There is more action, and in fact more sport, whether it happens that one or several leashes be slipped for the same animal. When it is not possible to know whose dogs have taken the game, it belongs to him who arrived first, providing that he has slipped his leash. So much for the foxes and hares, but the more interesting hunting of wolves remains. Few people except wolf-hunters—and they are reluctant to admit it—know how rarely old wolves are caught with hounds. All admit the danger of taking an old one either by a dagger thrust or alive from under* barzois, however good they be. There is always a possibilty they lose their grip, or to be thrown off just at the critical moment, but the greatest difficulty consists of the inability of the hounds to hold the wolf even when they have overtaken him.When its remembered that a full grown wolf is nearly twice as heavy as the average Borzoi and that pound for pound, he is stronger, it is clear that to overtake and hold him requires great speed and grit on the part of the pair of hounds. A famous kennel, Perchina, which two years since caught 46 wolves by the combined system, caught only one old wolf, that is three years or older. The same kennel last year caught 26, without a single old one among them.We likewise failed to include in our own capture, a single old wolf. I mention these facts to correct the false impression that exists with us, concerning the borzois, evidenced by the great disappointment when two years since, a pair in one of the western states, failed to kill outright a full grown timberwolf.

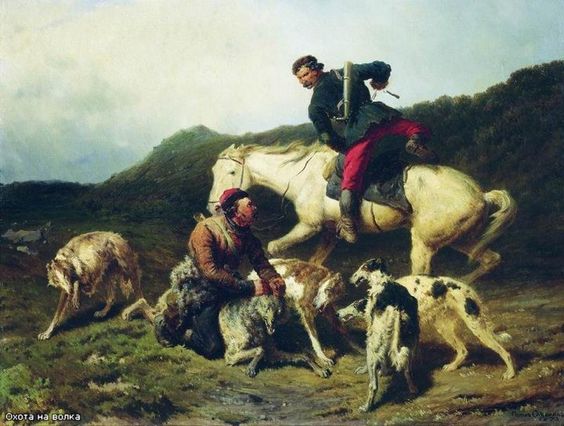

At the field trials on wolf, which take place twice a year at Colominaghi, near St Petersburg, immediately after the regular field trials on hares, I have seen as many as five leashes slipped before an old wolf could be taken, and then it was done only with the greatest difficulty. In fact, as much skill depends upon the borzatnik (huntsman) as the dogs. Almost the very second the dogs take hold he simply falls from his horse upon the wolf and endeavors to thrust the unbreakable handle of his nagaika between the jaws of the animal ; he then wraps the lash around the wolf’s nose and head. If the hounds are able to hold even a few seconds, the skilled borzatnik has had sufficient time, but there is danger even to the best. I saw an experienced man get a thumb terribly lacerated while muzzling a wolf, yet he succeeded, and in an incredibly short time. On another occasion, even before the brace of hounds had taken firm neck or ear holds, I saw a bold devil of a huntsman swing from his horse and in a twinkling lie prone upon an old wolf’s head. How this man, whose pluck I shall always admire, was able to muzzle the brute without injury to himself, and with inefficient support from his hounds is not easy to understand, though I was within a few yards of the struggle. Such skill comes from long experience, indifference to pain and, of course, pride in his profession. Having hunted foxes and hares, and having been shooting as often as the environs of Peschalkino and our time allowed, we changed our base to a village twenty-two versts distant over the border in the government of Yaroslay. It was a village like all others of this grain and Its district, where the livestock and poultry shared the same roof with their owners. A family of eleven wolves had been located about three versts from it by a pair of huntsmen sent some days in advance this explained our arrival.

In making this change, I do not now recall that we saw a single house other than those of the peasant villages and the churches. I fancy that in the course of time these peasants may have more enlightenment, a greater ownership in the land, and may possibly form a yeoman class. At the present the change, slow as it is, seems to point in that direction. With their limited possessions, they are happy and devoted subjects. The total of the interior decorations of every house consists of icons, of cheap colored pictures of the imperial family and of samovars. In our lodgings, the house of the village slarost, the three icons consumed a great part of the wall surface, and were burdened with decorations of various colored papers. No one has ever touched upon peasant life in Russia without mentioning the enormous brick stove (lezankce.); and having on various hunts profited by them, I mean to say a word in behalf of their advantages. Even as early as the middle of September the cold, continuous rains cause the gentle warmth of the kzattha to be cordially appreciated. On it and in its vicinity all temperatures may be found. Its top offers a fine place for keeping guns, ammunition and various articles free from moisture, and for drying boots, while the horizontal abutments constitute benches well adapted to thawing out a chilled marrow, or a sleeping place for those that like that sort of thing. A generous space is also allowed for cooking purposes. In point of architecture there is nothing that can be claimed for it but stability; excepting the interior upper surface of the oven, there is not a single curve to break its right lines. It harmonizes with the surroundings, and in a word answers all the requirements of the owner as well as of the hunter, who always preserves a warm remembrance of it.

The wolves were located in a large marshy wood and, from information of the scouts based on the midnight and dawn choruses, they were reported “at home.” Accordingly we prepared for our visit with the greatest precautions. When within a verst of the proposed curved line upon which we were to take our stands with barzois, all dismounted and proceeded through the marsh on foot, making as little noise as possible. The silence was occasionally broken by the efforts of the barzois to slip themselves after a cur belonging to one of the peasant beaters that insisted upon seeing the sport at the most aggravating distance for a sight hound. It was finally decided to slip one good barzoi that, it was supposed, could send the vexatious animal to another hunting ground but the cur, fortunately for himself, suddenly disappeared and did not show himself again.

After wading in miles of the marshy bog, we were at the beginning of the line of combat—if there was to be any. The posts along this line had been indicated by the chief huntsman by blazing the small pine trees or by hanging a heap of moss on them. The nine posts were established in silence along the arc of a circle at distances from each other of about 150 yards. My post was number four from the beginning. In rear of it and of the adjoining numbers a strong high cord fence was put up, because it was supposed that near this part of the line the old wolves would pass, and that the borzois might not be able to stop them. The existence of such fencing material as part of the outfit of a wolf-hunter is strong evidence of his estimate of a wolf’s strength—it speaks pages. The fence was concealed as much as possible, so that the wolf with borzois at his heels might not see it. The huntsmen stationed there to welcome him on his arrival were provided with fork-ended poles, intended to hold him by the neck to the ground until he was gagged and muzzled, or until he had received a fatal dagger thrust.

While we were forming the ambuscade—defensive line—the regular beaters, with 200 peasant men and women, and the fox-hounds, were forming the attack.

Everything seemed favorable except the incessant cold rain and wind. In our zeal to guard the usual crossings of the wolves, we ignored the direction of the wind, which the wolves, however, cleverly profited by. It could not have been very long after the hounds were let go before they fell upon the entire family of wolves, which they at once separated. The shouts and screams of the peasants, mingled with the noises of the several packs of hounds, held us in excited attention. Now and then this or that part of the pack would approach the line, and, returning, pass out of hearing in the extensive woods. The game had approached within scenting distance, and, in spite of the howling in the rear, had returned to part by the right or left flank of the beaters. As the barking of the hounds came near the line, the holders of the barzois, momentarily hoping to see a wolf or wolves, waited in almost breathless expectancy. Each one was prepared with a knife to rush upon an old wolf to support his pair; but unfortunately only two wolves came to our line, and they were not two years old. They were taken at the extreme left flank, so far away that I could not even see the killing. I was disappointed, and felt that a great mistake had been made in not paying sufficient attention to the direction of the wind. Where is the hunter who has not had his full share of disappointments when all prospects seemed favorable? As often happens, it was the persons occupying the least favorable places who had bagged the game. They said that in one case the barzois had held the wolf splendidly until the fatal thrust; but that in the other case it had been necessary to slip a second pair before it could be taken. These young wolves were considerably larger than old coyotes.

So great was the forest hunted that for nearly two hours we had occupied our posts listening to the spasmodic trailing of the hounds and the yelling of the peasants. Finally all the beaters and peasants reached our line, and the drive was over, with only two wolves taken from the family of eleven. Shivering with cold and thoroughly drenched. we returned in haste to shelter and dry clothes. The following morning we set out on our return to Peschalkino, mounted, with the barzois, while the fox-hounds were driven along the road. We marched straight across the country in a very thin skirmish line, regardless of fences, which were broken down and left to the owners to be repaired. By the time we had reached our destination, we had enjoyed some good sport and had taken several hares. The following morning the master of the imperial hunt, who had been kept at his estates near Moscow by illness in his family, arrived, fetching with him his horses and a number of his own hounds. We continued our hunting a number of days longer in that vicinity, both with and without fox-hounds, with varying success. Every day or two we also indulged in shooting for ptarmigan, black cocks, partridges, woodcocks and two kinds of snipe—all of which prefer the most fatiguing marshes.

One day our scouts arrived from Philipovo, twenty-six versts off, to report that another family of wolves, numbering about sixteen, had been located. The Amerikanka was sent in advance to Orodinatovo, whither we went by rail at a very early hour. This same rainy and cold autumnal landscape would be intolerable were it not brightened here and there by the red shirts and brilliant headkerchiefs of the peasants, the noise of the flail on the dirt-floor sheds and the ever-alluring attractions of the hunt.

During this short railway journey, and on the ride to Philipovo, I could not restrain certain reflections upon the life of the people and of the proprietors of this country. It seemed on this morning that three conditions were necessary to render a permanent habitation here endurable: neighbors, roads and a change of latitude; of the first two there are almost none, of latitude there is far too much. To be born in a country excuses its defects, and that alone is sufficient to account for the continuance of people under even worse conditions than those of these governments. It is true that the soil here does not produce fruit and vegetables like the Crimean coast, and that it does not, like the black belt, “laugh with a harvest when tickled with a hoe”; yet it produces, under the present system of cultivation, rye, and it’s sufficient to feed, clothe and pay taxes. What more could a peasant desire? With these provided his happiness is secured; how can it be called poor? Without questioning this defense, which has been made many times in his behalf, I would simply say that he is not poor as long as a famine or plague of some sort does not arrive—and then proceed with our journey.

From Orodinatovo to Philipovo is only ten versts, but over roads still less worthy of the name than the others already traveled. The Amerikanka was drawn by four horses abreast. The road in places follows the River Leet, on which Philipovo is situated. We had expected to proceed immediately to hunt the wolves, and nearly 3. peasant men and women had been engaged to aid the hounds as beaters. They had been assembled from far and near, and were congregated in the only street of Philipovo, in front of our future quarters, to await our arrival. What a motley assembly, what brilliancy of coloring! All were armed with sticks, and carried bags or cloths containing their rations of rye bread swung from the shoulders, or around the neck and over the back. How many pairs of boots were hung over the shoulders? Was it really the custom to wear boots on the shoulders? In any case it was de rigueur that each one show that he or she possessed such a luxury as a good pair of high top boots; but it was not a luxury to be abused or recklessly worn out. Their system of foot-gear has its advantages in that the same pair may be used by several members of a family, male and female alike.

It was not a pleasure for us to hear that the wolves had been at home at twilight and midnight, but were not there at dawn; much less comforting was this news to those peasants living at great distances who had no place near to pass the night. The same information was imparted the following day and the day following, until it began to appear doubtful whether we could longer delay in order to try for this very migratory pack.

Our chances of killing old wolves depended largely upon this drive, for it was doubtful whether we would make an attack upon the third family, two days distant from our quarters. Every possible precaution was taken to make it a success. I was, however, impressed with the fact that the most experienced members of the hunting party were the least sanguine about the old wolves.

Some one remarked that my hunting knife, with a six-inch blade, was rather short, and asked if I meant to try and take an old wolf. My reply was in the affirmative, for my intentions at that stage were to try anything in the form of a wolf. At this moment one of the land proprietors, who had joined our party, offered to exchange knives with me, saying that he had not the slightest intention of attacking a wolf older than two years, and that my knife was sufficient for that. I accepted his offer.

At a very early hour on this cold rainy autumnal morning we set out on our way to the marshy haunts of the game. Our party had just been reinforced by the arrival of the commander of the Empress’s Chevalier Guard regiment, an ardent sportsman, with his dogs. All the available fox-hounds, sixty in number, were brought out, and the three peasants counted off. The latter were keen, not only because a certain part of them had sportsmanlike inclinations, but also because each one received thirty copecks for participation in the drive. Besides this, they were interested in the extermination of beasts that were living upon their livestock.

The picture at the start was more than worthy of the results of the day, and it remains fresh in my mind. The greater portion of the peasants were taken in charge by the chid beater, with the hounds, while the others followed along with us and the barzois. Silence was enforced upon all. The line of posts was established as before, except that more care was exercised. Each principal post, where three barzois were held on leash, was strengthened by a man with a gun loaded with buckshot. The latter had instructions not to fire upon a wolf younger than two years, and not even upon an older one, until it was manifest that the barzois and their holder were unequal to the task.

My post was a good one, and my three dogs were apparently keen for anything. At the slightest noise they were ready to drag me off my feet through the marsh. Thanks to the nagazka, I was able to keep them in hand. One of the trio was well known for his grit in attacking wolves, the second was considered fair, while the third, a most promising two year-old, was on his first wolf-hunt. Supported by these three dogs, the long knife of the gentleman looking for young wolves and the yellow cuirassier officer with his shotgun, I longed for some beast that would give a struggle. The peasants accompanying us were posted out on each flank of our line, extending it until the extremities must have been separated by nearly two miles.

The signal was given, and hunters, peasants and hounds rushed into the woods. Almost instantly we heard the screams and yells of the nearest peasants, and in a short time the faint barking of the fox-hounds. As the sounds became more audible, it was evident that the hounds had split into three packs—conclusive that there were at Its three wolves. My chances were improving, and I was arranging my dogs most carefully, that they might be slipped evenly. My knife, too, was within convenient grasp, and the fox-hounds were pointing directly to me. Beastly luck! I saw my neighbor, the hunter of young wolves, slip his barzois, and like a flash they shot through the small pine trees, splashing as they went. From my point of view they had fallen upon an animal that strongly resembled one of themselves. In reality it was a yearling wolf, but he was making it interesting for the barzois as well as for all who witnessed the sight. The struggle did not last long, for soon two of the barzois had fastened their long teeth in him—one at the base of the ear, the other in the throat. Their holder hastened to the struggle, about 100 yards from his post, and with my knife gave the wolf the coup de grace. His dogs had first sighted the game, and therefore had the priority of right to the chase. So long as the game was in no danger of escaping, no neighboring dogs should be slipped. His third barzoi, on trial for qualifications as a wolf-hound, did not render the lea aid. Part of the fox-hounds were still running, and there was yet chance that my excited dogs might have their turn.

We waited impatiently until all sounds had died away and until the beaters had reached our line when further indulgence of hope was useless. Besides the above, the fox-hounds had caught and killed a yearling in the woods; and Colonel Dietz had taken with his celebrated Malodiets, aided by another dog, a two-year-old. What had become of the other wolves and where were most of the hounds? Without waiting to solve these problems, we collected what we could of our outfit and returned to Philipovo, leaving the task of finding the dogs to the whippers-in. The whys and wherefores of the hunt were thoroughly discussed at dinner, and it was agreed that most of the wolves had passed to the rear between the beaters. It was found out that the peasants, when a short distance in the woods, had through fear formed into squads instead of going singly or in pairs. This did not, however, diminish the disappointment at not taking at least one of the old ones. The result of this drive logically brought up the question of the best way to drive game. In certain districts of Poland deer are driven from the line of posta and the same can be said about successful Moose hunts of Northern Russia. Perhaps that way may also be better for wolves.After careful consideration of the hunting situation we were unanimous in prefering hare and fox with both Foxhounds and Barzois or with the latter alone, at discretion, to the uncertainty of wolfhunting; so we decided to change our locality. Accordingly, in the following day we proceeded in the Amerikanka, to the town of Koy, 25 versts distant.

We arrived about noon and were quartered in a vacant house in the large yard of Madame Ponamaroff. Our retinue of huntsmen, dogs, horses, ambulance and wagons arrived an hour later.

There was no more wolf-hunting.

Henry T. Allen

Year of Event:

Country:

Personal Collections:

Source:

Author:

Dogs:

Persons: