LnRiLWZpZWxke21hcmdpbi1ib3R0b206MC43NmVtfS50Yi1maWVsZC0tbGVmdHt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmxlZnR9LnRiLWZpZWxkLS1jZW50ZXJ7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWZpZWxkLS1yaWdodHt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOnJpZ2h0fS50Yi1maWVsZF9fc2t5cGVfcHJldmlld3twYWRkaW5nOjEwcHggMjBweDtib3JkZXItcmFkaXVzOjNweDtjb2xvcjojZmZmO2JhY2tncm91bmQ6IzAwYWZlZTtkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9ja311bC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGVze21hcmdpbjowfQ==

LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjcwNzhmNzFkYmZmNDFmOWVlNDZiZmE2MWRiOGZkOTE1Il0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNWZyKTtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6IDBweDtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjcwNzhmNzFkYmZmNDFmOWVlNDZiZmE2MWRiOGZkOTE1Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjcwNzhmNzFkYmZmNDFmOWVlNDZiZmE2MWRiOGZkOTE1Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0udGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9ICAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iZjRlNzY0MzFlYzRjMjFmNzBhMTkxNTJmZmQxMmMzNzUiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMzMzMzMzMzMzMzMzMzNmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMzMzMzMzMzMzMzMzMzNmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMzMzMzMzMzMzMzMzMzNmcik7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOiA2cHg7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOiAwcHg7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmNGU3NjQzMWVjNGMyMWY3MGExOTE1MmZmZDEyYzM3NSJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDNuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmNGU3NjQzMWVjNGMyMWY3MGExOTE1MmZmZDEyYzM3NSJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDNuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmNGU3NjQzMWVjNGMyMWY3MGExOTE1MmZmZDEyYzM3NSJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDNuICsgMykgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIzMDM0ZmJlODg2YzExMDU0ZTk1YjQ2YjA5ZDNlNDExMiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSBAbWVkaWEgb25seSBzY3JlZW4gYW5kIChtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDc4MXB4KSB7IC50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI3MDc4ZjcxZGJmZjQxZjllZTQ2YmZhNjFkYjhmZDkxNSJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC41ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI3MDc4ZjcxZGJmZjQxZjllZTQ2YmZhNjFkYjhmZDkxNSJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI3MDc4ZjcxZGJmZjQxZjllZTQ2YmZhNjFkYjhmZDkxNSJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9IC50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0udGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAgLnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImY0ZTc2NDMxZWM0YzIxZjcwYTE5MTUyZmZkMTJjMzc1Il0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImY0ZTc2NDMxZWM0YzIxZjcwYTE5MTUyZmZkMTJjMzc1Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImY0ZTc2NDMxZWM0YzIxZjcwYTE5MTUyZmZkMTJjMzc1Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjMwMzRmYmU4ODZjMTEwNTRlOTViNDZiMDlkM2U0MTEyIl0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9ICB9IEBtZWRpYSBvbmx5IHNjcmVlbiBhbmQgKG1heC13aWR0aDogNTk5cHgpIHsgLnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjcwNzhmNzFkYmZmNDFmOWVlNDZiZmE2MWRiOGZkOTE1Il0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iNzA3OGY3MWRiZmY0MWY5ZWU0NmJmYTYxZGI4ZmQ5MTUiXSAgPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMW4rMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0udGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAgLnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImY0ZTc2NDMxZWM0YzIxZjcwYTE5MTUyZmZkMTJjMzc1Il0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iZjRlNzY0MzFlYzRjMjFmNzBhMTkxNTJmZmQxMmMzNzUiXSAgPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMW4rMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIzMDM0ZmJlODg2YzExMDU0ZTk1YjQ2YjA5ZDNlNDExMiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAgfSA=

The Borzoi

H.W. Huntington, Marlborough Kennels, 1898; published in “Outing: Sport, Adventure, Travel, Fiction”

Far-off Russia, where winters are so severe that but for a few months in the entire year are the fields free from snow, is the home of a breed of dogs known there as the Borzoi, or Psovie. The dogs are grand in aspect, with long, flowing coats of silken texture that defy the terrible cold, and they are built on lines that speak volumes for the antiquity of their origin. In this country they are known as Russian wolfhounds.

The first speciman of the breed ever exhibited here was the property of Mrs. Edw. Kelly, who, seeing it in Paris late in the eighties, recognized its great beauty and showed it at the Westminster Kennel Club Show, where it created a decided sensation. Since that time some of our enthusiasts have imported the best specimens to be had in continental Europe, and today our exhibits at the various shows are well worth seeing.

England is the country that has perhaps done most for the breed. Some fifteen years ago the Brito secured the best that Russia had and bred them with the exceeding judgement he displays in such matters. He today possesses beyond question some of the grandest living. Within the past few years, however, Germany has made most wonderful strides in breeding these dogs, and together with the Britons has brought them very rapidly to the fore. It seems to be a breed particularly adapted to the Germans and their climate, which may perhaps in some degree account for the success they are reaping in the breeding. In fact, so much has the breed degenerated in Russia for want of intelligent mating, that one of our greatest German fanciers and judges of the breed claims that the purchasers of good specimens must  hereafter look to Germany and Great Britain for what they want, and never think of seeking anything in Russia. The proof of the lack of knowing the essential and correct points of the breed on the part of the Russians was never more forcibly shown than some three years ago, when the Czar of Russia sent over to one of the great English shows a choice draught from his kennels. With the exception of one exhibit these dogs were not in any particular equal to the English-bred ones.

hereafter look to Germany and Great Britain for what they want, and never think of seeking anything in Russia. The proof of the lack of knowing the essential and correct points of the breed on the part of the Russians was never more forcibly shown than some three years ago, when the Czar of Russia sent over to one of the great English shows a choice draught from his kennels. With the exception of one exhibit these dogs were not in any particular equal to the English-bred ones.

The Czar presented to the Prince of Wales Molodetz and Owdalzka, which were considered the choice of his kennels, but when they reached England they were found to be not nearly so good as some other dogs not born in the purple, as it were.

Lady Emily Peel and the Rev. J. Cumings Macdonna were the first of English enthusiasts to show these dogs in London, and there in the streets it was a common sight to see her ladyship with her two white dogs that created universal admiration wherever they appeared.

Later on the Duchess of Newcastle, Mrs. Col. Wellesley, Messrs. Muir, Blees, Dobbleman, Musgrave, Labouchere, and Prince Demidoff became sponsors for this magnificent breed, and under their fostering care it is hardly to be wondered that the improvement has been great.

The earliest of the finest specimens belonged to Colonel Wellesley, and with his Krilutt in the stud he probably did more for the advancement of the breed than any one else. Oudar and Korotai also have been very instrumental in producing good stock, so naught remains now but judicious breeding to bring the Borzoi to a state bordering on absolute perfection according to the standard for this breed. Bytschock, owned by Mr. Vallmer, undoubtedly stands today at the head of all the Borzois of continental Europe, and, while standing full thirty-two inches at the shoulder, is most symmetrically made. Gaimane, however, is making a great bid for first honors, and when they meet excitement runs high. Five thousand marks have been offered for the former by Mr. Kraus, one of our American enthusiasts, but the offer was refused. Tartar, another great dog owned in Germany, has gone the way of all dog flesh. He during his lifetime was considered by many to be the equal of England’s champions.

There seems to be a fascination about the dog that few can resist, and where once it has gained a warm corner in the heart no other breed can take its place.

The Duchess of Newcastle, who recently entered the judging ring, donning the ermine for the first time and adjudicating upon the merits of the exhibits with great success, is now the most enthusiastic admirer of the Borzoi in England, while Mr. Kalmountzky holds the same position in Russia, he having recently given 25,000 rubles for a young dog. He expended in one year over 42,000 rubles in endeavoring to make his collection the finest in the world.

In the steppes of Russia, where wolves are so numerous, as well as throughout the entire realm, the Borzoi is used for hunting these beasts, which, in severe winters, will encroach upon towns, and even cities, attacking men and children alike, while sheep and cattle seem to be their especial prey.

When driven by hunger, the wolves stop at nothing, attacking and killing horses and cows. In addition to being large and heavy, the wolves are exceedingly cunning, and try not only the patience but the ingenuity of the hunter to catch them. It will, therefore, be seen that only a large and powerful dog endowed with great speed and courage is able to cope with them, and nature seems to have well provided the Borzoi for this purpose.

Nearly all dogs used in hunting wild animals not only

attack but endeavor to kill their quarry, but with the Borzoi it is entirely different. At an early age they are put into training with old and experienced dogs, so they soon learn how to properly attack their adversary.

The forests are full of wolves, so when a hunt is instituted the hunters assemble at stated places, each with a pack of hounds varying in number from eight to twenty. Beaters are sent deep into the forest hours before the hunt begins to drive the wolves out into the open. After these beasts are well in view, four Borzois generally are let loose as a team from slips, the same as are used in England in greyhound coursing, and then begins the race for life, for when once overtaken by the dogs the wolves know that death is soon to follow. The wolf and the dog being both of the same genus, one knows all the tricks of the other; hence, it is like the traditional Greek meeting Greek.

As soon as the wolf is sighted and the dogs slipped, the hunters, generally on horseback, follow as close as possible, and watch for the opportune moment in which to attack and kill their prey. When one of the dogs gets nearly side by side with the wolf he makes one bold spurt, and with the foreshoulder strikes the wolf so that he is knocked over. The other dogs coming up, each strikes him in the same manner as he tries to rise, or they pin him to the earth, and so engage him till the hunter arrives, who, with spear or knife, kills him.

In general appearance the Borzoi resembles a large English greyhound, but with long silky coat, attentuated head, and rather flat-sided body. The standard adopted calls for a very long and lean head throughout, with a flat, narrow skull, long snout, and hardly any perceptible stop. Though it is of this delicate outline, it should be covered with strong muscles, giving the appearance of being very powerful, for the duties it has to perform require that it should be without the faintest trace of weakness.

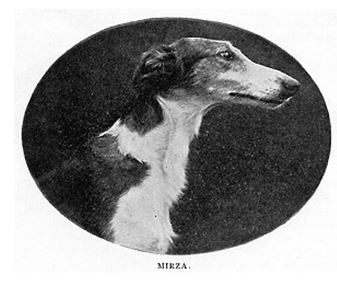

The nose is black, and, though rarely found, should be what is known as the Roman nose, and is, perhaps, more fully developed in Champion Argoss than in any other dog in America. The eyes are one of the most beautiful features of the dog, being dark, expressive and oblong. In our best specimens they are very gentle, soft and dreamy when in repose, but, when excited, are full of fire and exceeding determination. The ears are very small, thin of leather, set high on the head, with the tips almost touching each other when thrown back, and, when covered, as they should be, with soft, fine hair, they add  greatly to the elegant appearance of the head.

greatly to the elegant appearance of the head.

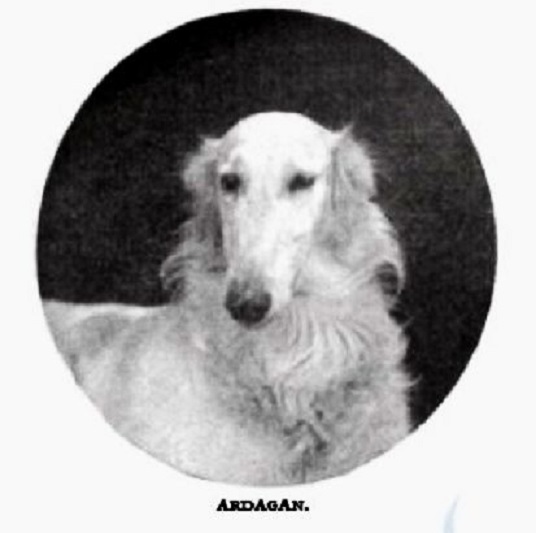

There are two distinctive types of heads, although the general outline of form is the same. As it is almost impossible to describe the characteristics of both, the reader is referred to the reproduction of the heads of Argoss and Ardagan, each representing the ideal of its own type. At the English shows the fancy turns toward the type of the latter, while the Russians prefer the former, as representing more what is desired in a dog whose chief object is to hunt the wolf. This, however, is largely a matter of fancy. The head is on the general outline of the greyhound, only it is very much longer and more attentuated, some good specimens measuring eleven inches from tip of nose to occiput, and, in point of narrowness, far exceeding that of the greyhound. Taken all in all, it is one of the most ideal of heads, and perhaps is best shown in that of Champion Argoss, the celebrated dog the writer imported some years ago, and with which he won fifty-eight first and special prizes.

While the standard calls for a neck “not too short,” it is far better to err on the side of being too long than being too short, especially as all good specimens should be provided with what is called a profuse ruff, and which gives the head a most elegant, as well as quaint, appearance. This characteristic feature of the breed is best shown in the vignette of Mr. Kraus’s Ardagan.

While the standard calls for a neck “not too short,” it is far better to err on the side of being too long than being too short, especially as all good specimens should be provided with what is called a profuse ruff, and which gives the head a most elegant, as well as quaint, appearance. This characteristic feature of the breed is best shown in the vignette of Mr. Kraus’s Ardagan.

In the males the back is somewhat arched, while in females it should be level and broad. The loins are broad and drooping, the ribs deep, reaching about to the elbows, but not so well sprung as in the greyhound.

Why the standard should call for ribs of less spring than the greyhound’s is inexplicable. Both are dogs of the chase, and well-spring ribs are the sine qua non of a fast running dog. The standard adopted by our fanciers for the breeding of every member of the hound family, down to the diminutive Italian greyhound, calls for well-sprung ribs, as such insure greater room for the action of the lungs and heart.

The forelegs are very straight and muscular, the hindlegs being thrown somewhat under the body, which gives the dog at times a rather stilty appearance. While the clause seems to have been made to fit certain dogs, it certainly is better to have an easy-moving dog for the chase than one which is, or at least appears to be, tucked up. Some of our best and most intelligent fanciers are now trying to breed out this peculiarity of the position of the hindlegs, and it seems a rational effort. It certainly will tend to improve the outline of the dog, and many claim it will add greatly to its speed.

The coat varies with the particular breed, as there are two recognized breeds of this dog, viz., Chesto-psovie and Gustopsovie. One is recognized as of the Circassian type, better for deep snow, as the snow then will not adhere to the dog, and so wet and chill him. The other is the long, silky, flowing coat, of wonderful texture, and on the body reaching sometimes to a length of five inches, while on the tail it should be of great length, the writer having had one female whose hair measured there fourteen inches. The more profuse and silky the coat the better, and it should always be a factor when purchasing.

Quality as well as quantity should be taken into consideration. A woolly coat is as objectionable in a Russian wolfhound as in a setter, and should so be penalized. Curly coats are much to be avoided, though some rare-made specimens have them. Those of some of our best specimens are a trifle wavy, which by many is considered far preferable to the flat-lying coat. The tail is one of the most beautiful features of the dog. It is very long, sickle-shaped, set on low, and gracefully carried. It should be heavily covered with long silky hair – the longer the better – parted in the center and falling gracefully over the sides.

The height of good specimens in males ranges from twenty-eight to thirty-three inches, and in females from twenty-six to thirty inches, and in every case, where all things are equal, preference should be given to the larger specimens, as they are accordingly more beautiful and useful. It is quite easy to breed good small specimens, for in them the faults are not so glaring, but it is very difficult to raise fine large ones, as in them any defects are greatly accentuated and cannot be overlooked. But in no case should height or size be made supreme, as, unless there is proportionate power and bone, height and size are worse than useless, as we then have a flat-sided shelly animal that is of no earthly good.

The legs and feet of the Borzoi are somewhat different from the English greyhound’s. The legs of the former are what the Russians call “lean”, or what we would term flat in bone, while in the latter they are more inclined to be round. In fact, it seems in many Borzois imported from Russia that the breeders had tried to discover how wholly flat a dog they could possibly produce. The feet are very long, but the toes are close together, between which there is a profusion of soft hair. As the work has to be done largely over snow, feet formed as called for by the standard will do well enough, but where frozen earth is to be traversed the dog would soon grow footsore, and a broken toe or two would not be uncommon; in fact, four of the best wolfhounds we now have here have broken toes. Shorter toes, after the style of the English greyhound’s, are decidedly preferable, as being far more serviceable.

His wonderfully long attentuated head, his style, character, love for his master and intelligence; his form, the most graceful of any of the canine race; his coat, profuse and silk-like in texture, all combine to stamp the Borzoi the aristocrat of the entire canine race, and as a companion, either on foot or horseback, none better can be found the world over.

The question of color has been a vexed one both here and in England, and it was only until recently that it was publicly admitted that the writer’s claim, made years ago, was correct, viz., that the Borzoi can be any color. Champion Argoss, who, beyond all doubt, was the greatest all-round Borzoi ever shown in America, was black, white and tan, with a preponderance of black; and when in Russia he won the great silver medal at Moscow in 1891, the award being made in Russia and under a native judge proved his right of color. Still, classified as a recognized color, there is no question but that the most beautiful color is either pure white, white and orange, white and lemon, or white and silver-gray. Pure white with mahogany patches is also extremely beautiful. There is now a standing offer of £200 for a solid pure silver dog, and yet no takers are to be found, as this color is very rare indeed.

Much harm has been done the Borzoi in this country by the statements made by prejudiced and unreliable writers that he was dangerous, treacherous and wholly unreliable. These statements were a gross libel. There are vicious specimens in every breed of dogs, but among the hunters there is perhaps none more docile, more lovable, more tractable than the Russian wolfhound or Borzoi. None loves the companionship of the human race more than he, and when kindly treated he is all the most exacting dog fancier could desire either as a companion or a hunter.

Much harm has been done the Borzoi in this country by the statements made by prejudiced and unreliable writers that he was dangerous, treacherous and wholly unreliable. These statements were a gross libel. There are vicious specimens in every breed of dogs, but among the hunters there is perhaps none more docile, more lovable, more tractable than the Russian wolfhound or Borzoi. None loves the companionship of the human race more than he, and when kindly treated he is all the most exacting dog fancier could desire either as a companion or a hunter.

At the Brooklyn show several years ago the impression of his ferocity had gained such strength by malicious writings that one exhibitor, to prove the falsity of the statements, put his own little child into the stalls of every Borzoi benched there. Child-like, he pulled their ears, thrust his chubby fists into their mouths, walked on their feet, pulled their tails to his heart’s content, finally closing the scene by selecting one beautiful white bitch as his especial favorite, and falling asleep with his head across her loins. The bitch, from time to time, would raise her head, gently lick the face of the sweet young sleeper, then sleep herself. This one public proof of the lovable character of the dog did more toward disproving the falsity of the reports than pages of denials.

hereafter look to Germany and Great Britain for what they want, and never think of seeking anything in Russia. The proof of the lack of knowing the essential and correct points of the breed on the part of the Russians was never more forcibly shown than some three years ago, when the Czar of Russia sent over to one of the great English shows a choice draught from his kennels. With the exception of one exhibit these dogs were not in any particular equal to the English-bred ones.

greatly to the elegant appearance of the head.

While the standard calls for a neck “not too short,” it is far better to err on the side of being too long than being too short, especially as all good specimens should be provided with what is called a profuse ruff, and which gives the head a most elegant, as well as quaint, appearance. This characteristic feature of the breed is best shown in the vignette of Mr. Kraus’s Ardagan.

Much harm has been done the Borzoi in this country by the statements made by prejudiced and unreliable writers that he was dangerous, treacherous and wholly unreliable. These statements were a gross libel. There are vicious specimens in every breed of dogs, but among the hunters there is perhaps none more docile, more lovable, more tractable than the Russian wolfhound or Borzoi. None loves the companionship of the human race more than he, and when kindly treated he is all the most exacting dog fancier could desire either as a companion or a hunter.