From the New Book of the Dog edited by J. Sidney Turner, Chairman of the Committee of the Kennel Club. Published in 1907. The Borzoi section was written by Major S.P. Borman of the Ramsden kennels.

Although known in this country as the Borzoi, or Russian Wolfhound, this dog belongs to the Greyhound family – is, in fact, the Russian Greyhound of “Psovoi”, and is closely allied to that large group of Eastern Greyhounds which includes the Persian, the Circassian Orloff Hound, and others. No doubt all these dogs originated from one common stock, the characteristics of the various varieties probably being caused by different crosses, and also, to some extent, by climactic influences.

The Borzoi in its native land is by no means a “poor man’s dog,” being kept principally by the nobles and rich landowners for hunting purposes, the various strains of the leading kennels being jealously guarded and seldom disposed of. Certain it is, that, even in Russia, really good specimens are hard to obtain, for as falconry was the national pastime of the Englishman in “ye goode olde days,” so is coursing that of the Russian, and he values his best hounds far too highly to part with them.

Indeed, a more fasinating form of sport than Wolfhunting can hardly be imagined. One method adopted, and perhaps the most popular, is as follows: Wolves having been located in a wood, the hunt proceeds there on horseback, each hunter holding in his left hand a “leash” of Borzois, as nearly matched in speed, size and colour as possible – generally two dogs and a bitch. Arrived on the scene of action, the chief huntsman stations the remainder every hundred yards or so round the wood, and a pack of Foxhounds is sent in to draw it. Should a wolf break covert and make for the open the nearest hunter, putting his horse at a gallop, slips his hounds. These are after their game like lightning, each hound endeavouring to seize the wolf behind the ears in such a manner that he cannot use his teeth, holding him until the hunter arrives, who, throwing himself from his horse, gives the coup de grace with his hunting knife; or perhaps the Wolf is taken alive and sent to the kennels, for the purpose of training the young dogs to get their neck-hold, as not until they have mastered this grip are they considered fit to take their part in field work. (As an interesting example of hereditary instinct, one has only to watch young Borzoi pups playing or squabbling among themselves, and it will be noticed that they invariably seek to obtain this “neck-gold”.).

Another form is called Field-hunting. In this case the hunters advance across the open country at intervals of 200 yards or so, slipping the hounds at any game they may put up, such as foxes and hares. Trials are also held, taking place in an enclosure railed in with a high fence. The wolves are brought in carts similar to our deer carts. A brace of dogs is loosed, and the whole merit of the course consists in the manner and power with which the dogs can hold the wolf, so that the keepers can secure him alive. It follows, therefore, that the dogs must be of equal speed; one dog alone would be unable to hold the quarry. It will thus be seen that in Russia the dog is not used for hunting the wolf only, but hares and smaller game; and it is a pity that some coursing-man does not take up the breed over here; properly trained, the Borzoi should hold its own with the Greyhound. Many dogs the writer has possessed have been excellent at both hares and rabbits.

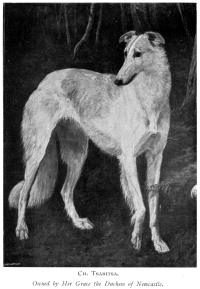

It must now be some thirty years since the first Borzois were imported into England, when an occasional specimen was shown in “variety” classes, being generally catalogued as a “Siberian Wolfhound.” But the credit of being the founder of a large kennel of these aristocratic hounds belongs, undoubtedly, to the Duchess of Newcastle, who, between the years 1889 and 1892, imported several good specimens, among others Champion Osslad, Kaissack, Champion Golub, Champion Milka and Oudar. In 1894 the breed was granted a separate classification in the Kennel Club Stud Book (Vol. xxi.).

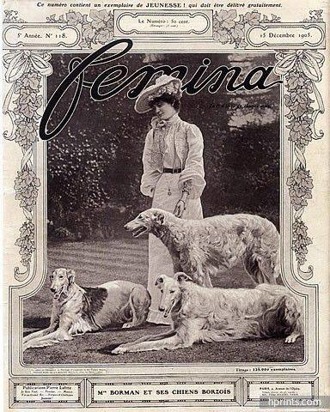

About 1895, the breed fairly “caught on” and has continued to make rapid strides in public favour, as witness the entries obtained at many shows where a good classification is given; 80 to 100 being by no means a record. Why? The answer is easy. To those who do not know what a Borzoi is, the writer would say, in the words of our neighbours across the channel, “picture to yourself” a dog combining at once the size and strength of the Deerhound, the speed of the Greyhound, the symmetry of the Whippet, with a long, silky coat (glistening white predominating), and a head, the length of which is unique, and possessed by no other breed. Add to these attractions the fact that the dog is affectionate, cannot be excelled as a lady’s companion (by the way, practically all the leading kennels are owned by ladies), makes an excellent house dog, and last, but not least, requires no “trimming” before he can be exhibited! Are not these sufficient reasons for the popularity attained in so short a time by this breed?

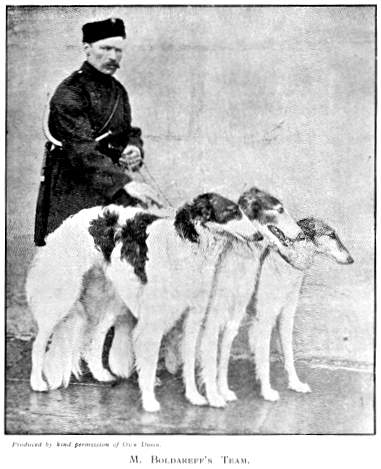

Below is given a list of points as adopted by the Borzoi Club, to which are added a few explanatory notes (in brackets), for the further guidance of the novice; but if the reader will refer to the illustration of the leash of Russian hounds here produced , he will find this of more educational value than any amount of printed matter. This wonderful team, from the Woronzova hunt, owned by Mr Boldareff, is said to be the best in Russia, and in the writer’s opinon there is nothing as yet in this country to touch them, although we are gradually approaching the type.

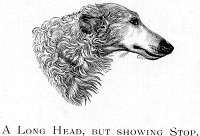

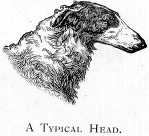

Head – should be long and lean. [It is, however, not only essential for the head to be long, but it must also be what is termed well balanced, i.e., the length from the tip of the nose to the eyes must be the same as from the eyes to the occiput. A dog may have a long head but the length may be all in front of the eyes.]

The skull should be flat and narrow, stop not perceptible. [Too much stress cannot be laid on the importance of the head being well filled up between the eyes] and the muzzle long and tapering. The head from forehead to the tip of the nose should be so fine that the shape and direction of the principal veins and bones can be clearly seen; and in profile should appear rather Roman-nosed. Bitches should be even narrower in head than dogs.

Eyes – Dark, expressive, almond-shaped, and not too far apart. Ears – Like those of a greyhound, small, thin, and placed well back on the head, with the tip, when thrown back, almost touching behind the occiput. [It is not a fault if the dog can raise his ears erect when excited or looking after game. They should, however, be carried as above at other times.] Neck – The head should be carried somewhat low, with the neck continuing the line of the back. Shoulders – Should be clean and sloping well back, [i.e., the shoulder blades should almost meet.] Chest – Deep and somewhat narrow. [The chest must be capacious, but the capacity must be derived from depth, and not from “barrel-ribs,” a bad fault in a running hound.] Back – Rather long, and free from any cavity in the spinal column, the arch in the back being more marked in the dog than in the bitch. [This arch is an important point and one of the characteristics of the breed. The writer likes to see the arch well developed in the bitch also.] Loins – Broad and very powerful, with plenty of muscular development. Thighs – Long and well developed, with good second thigh. Ribs– Slightly spring at the angle of the ribs, deep, reaching to elbow or even lower. Fore-legs – Lean and straight; seen from the front they should be narrow, and from the side, broad at the shoulders and narrowing gradually down to the foot, the bones appearing flat, and not round as in the Foxhound. Hind-legs – The least thing under the body when standing still, not straight, and the stifles slightly bent. [That is to say, the legs must be straight as regards one another, i.e., not cow-hocked; but the stifles and hocks should be bent. Straight hind-legs imply want of speed.] Muscles – Well distributed and higly developed. Pasterns – Should be strong. Feet – Like those of the deerhound, rather long, the toes close together and well arched. Coat – Long, silky (not woolly), either flat, wavy or slightly curly. On the head, ears, and front legs it should be short and smooth. On the neck the frill should be profuse and rather curly. On the chest and rest of the body, the tail and hind-quarters, it should be long. The fore-legs should be well-feathered. Tail – Long and well-feathered, and not carried gaily. Height – *At shoulder of dogs, from 29 in. upwards; of bitches, from 27 in. upwards [It must be borne in mind that few dogs of 29 in. would win in the show-ring at the present day unless particularly good in all other respects, most of the present day winners averaging from 31 to 32 inches.] Faults – Head short and thick; too much stop; parti-coloured nose; eyes too wide apart; heavy ears; heavy shoulders; wide chest; barrel-ribbed; dew-claws; elbow turned out; wide behind. [The Club standard does not mention light-coloured eyes and over-shot jaws, both of which are undoubtedly bad faults.]Colour – Immaterial, provided white predominates. Fawn, brindle, lemon, slate-blue, orange and black markings are seen. Black-and-tan is less liked. Whole or self-coloured dogs are also met with, but are not greatly favoured. Of all white dogs, few have been seen on the show bench of late years.

The uninitiated may say, “It is all very well to tell us that the head must be long, but what is long?” Therefore, below are given the measurements of some of the leading dogs, past and present, with their pedigrees, which latter should prove of use to the intending breeder.

First let us take a few of those which some years ago were “at the top” of their breed. Although no longer with us, their names appear in the pedigrees of most of the present day “cracks,” and a short summary of their good and bad qualities may be helpful to breeders; for it is to these former ancestors that many of their pups will “throw back,” and unless one knows the points possessed by the stud dog’s and brood bitch’s ancestors, it is difficult to breed with any degree of certainty.

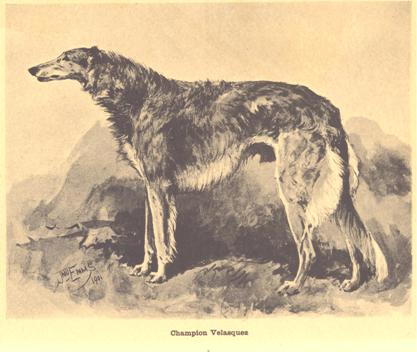

Perhaps one of the most successful dogs on the show nech was Ch . Velsk(95), owned by Her Grace the Duchess of Newcastle. Almost white, with faint, light grey markings, this dog possessed a marvellous coat, great depth of chest and plenty of bone. He was unfortunately rather lacking in arch – his worst fault. His measurements were as follow: – Height at shoulder, 31 3/4 in.; length of head, 12 1/2 in.; girth of chest, 35 1/2 in. CHAMPION VELASQUEZ, his litter brother, a handsome whole-coloured brindle, was a more racily built and bigger dog. He left few descendants in this country before being exported to America.

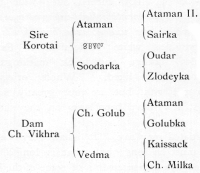

The pedigree of these two dogs (Champions Velsk and Velasquez) is as follows:

CHAMPION STATESMAN (still alive, but retired on his laurels) and his brother, CH. SHOWMAN, were also big winners some four or five years ago. Both were big, sound dogs, with light fawn markings. Their names occur in many of the present-day pedigrees. Their pedigree (which, as an example of in-breeding, is of interest alone) is as follows:

Their dam, Windle Princess, by Korotai ex Windle Snow, was litter sister to Ch. Windle Courtier. Courtier was all quality; some say he was too flat-sided and too curly in coat; but there is doubt that for quality, more especially in head, one must look to dogs containing blood of the “Windle” strain, at least, that is the writer’s experience. This kennel, owned by a Mr. Coop, was dispersed some years ago.

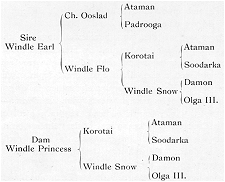

Perhaps the biggest Borzoi, combining size and quality was Ch. Caspian, who when standing smartly, measured 34 1/2 in., length of head 12 3/4 in., girth of chest 37 1/2 in. Unfortunately he, too, left few descendants, dying when less than three years old.

By the kindness of the Duchess of Newcastle, the writer is enabled to include an illustration of her celebrated imported bitch Ch. Tsaritsa. A big, sound bitch, her measurements equalled those of many dogs, as a glance will show: – Height 31 1/2 in., length of head 11 1/2 in., girth 35 1/2 in. She was exhibited as “pedigree unknown.” Her success on the show bench was phenomenal. She won no less than 66 firsts, specials and championships

Although not a full champion, a dog that deserves mention as having left his mark on the breed is Piostri, a tall lemon-marked dog by Windle Earl ex Alston Queen, by Ch. Windle Courtier. He was extremely prepotent, stamping his wonderful head on nearly all his progeny. He covered perhaps too much ground, and wanted more substance; but with all his faults, his early death was a great loss to the breed.

The list would not be complete without mentioning some of those bitches, dams and grand-dams of our present champions whose names appear in all the best pedigrees. Foremost among these rank Ch. Vikhra, dam of Ch. Velsk, Ch. Velasquez, and of White Tsar; and Ina, dam of Champions Caspian, Vassal, Kieff and others. Ina was just a fair specimen, and never made a great name on the show bench, but as a brood bitch she was simply invaluable, as was Windle Princess, a tall white bitch, dam of Champions Sunbeam, Statesman, Showman, etc.

And now to turn to some of the present-day champions. These can be seen at any big show, and criticism here would be out of place. The writer, therefore, merely appends their pedigrees and measurements; for the latter he is indebted to their respective owners.

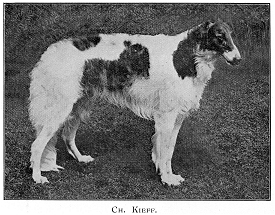

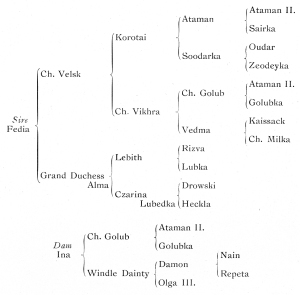

First let us bracket together the brothers Champions Vassal and Kieff (later litter), and give an extended pedigree, from which names occurring in following pedigree may be traced back.

Both these dogs, built on much the same lines, are brindle marked. Ch. Kieff’s measurements are: height, 33 in., head, 12 1/2 in., girth, 35 1/2 in.

Another good dog by Fedia is Ch. Padiham Nordia. His dam, Norah, is a Windle-bred bitch, by Korotai ex Windle Dainty; Nordia is also brindle-marked. Height, 32 1/2 in., head, 12 in., girth, 36 in.

Closely related to the above is Ch. Berris, one of the few sired by Ch. Caspian. His dam, Selwood Strelka, was by Ch. Krilutt ex Nagla II. Height 34 in., girth 37 in., head 13 in. Ch. Ivan Turgeneff, by White Tsar ex Ch. Sunbeam. Colour, white, with fawn markings, half Windle-bred, his dam being full sister to Ch. Statesman. Height 32 1/2 in., girth 40 in., head 13 1/2 in.

In Ch. Strawberry King, by Ch. Kieff ex Maid of Honour (by Ch. Windle Courtier), we have got another with Windle blood on both sire and dams’ sides; markings, light brindle.

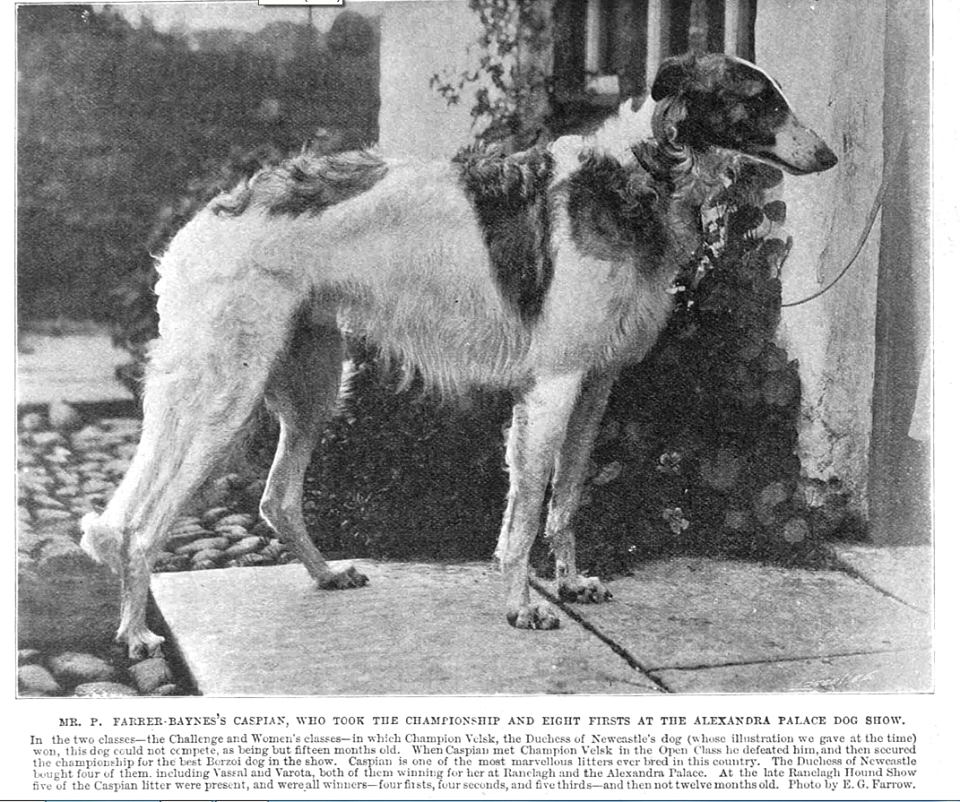

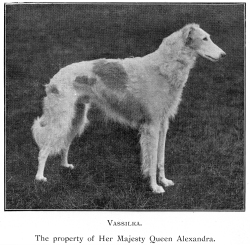

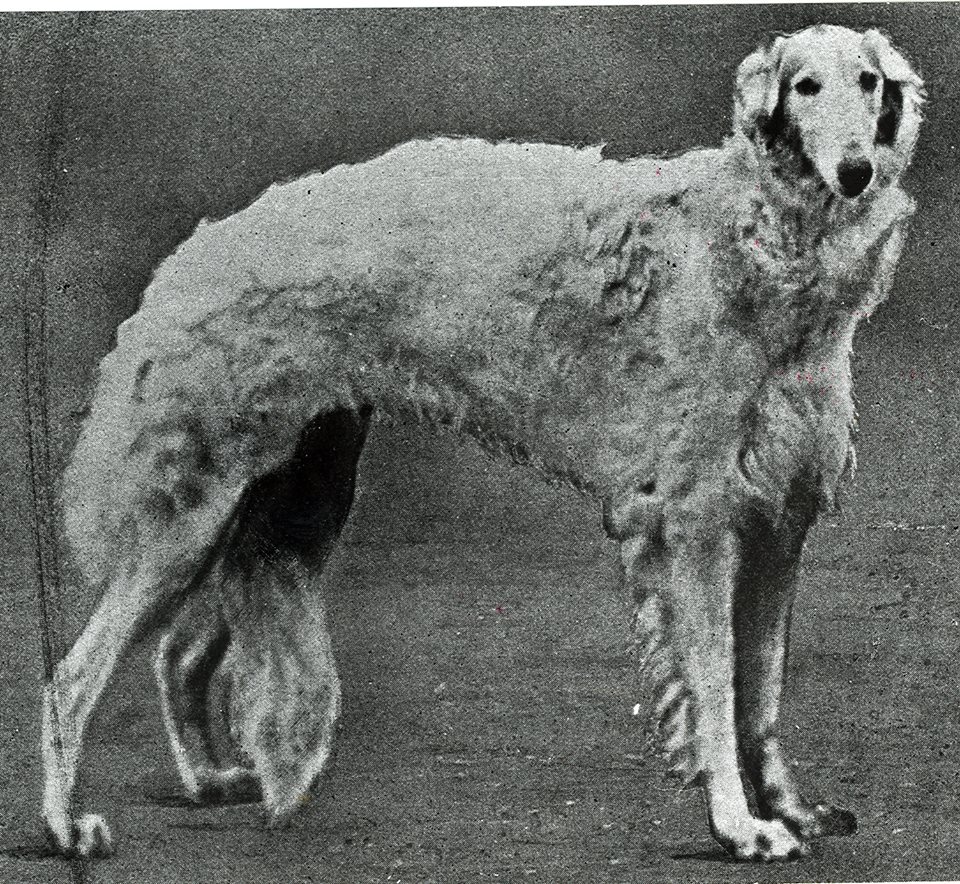

H.M. the Queen’s Borzoi Vassilka, a capital photo os which appears here, is by Ch. Velsk. His mother, Gatchina, is an imported bitch, the pedigree of which is unknown. He stands 32 1/2 in. at shoulder, length of head 12 1/2 in., girth 35 ins., markings, light fawn.

Of the bitches on the show bench at the present time, it is perhaps invidious to mention names where many are so good: but the writer thinks it will be admitted that

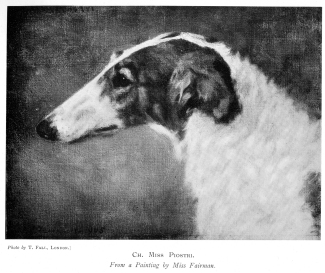

Ch. Sunbeam and Ch. Miss Piostri head the list. A photo of a painting of the latter by the eminent canine artist, Miss Fairman.

The dogs living at the time of writing and entitled to the coveted prefix of “Champion” are:

-

- Clumber Kennels (Her Grace the Duchess of Newcastle):

Dogs – Chs. Ivan Turgeneff, Velsk Votrio, and Vassal

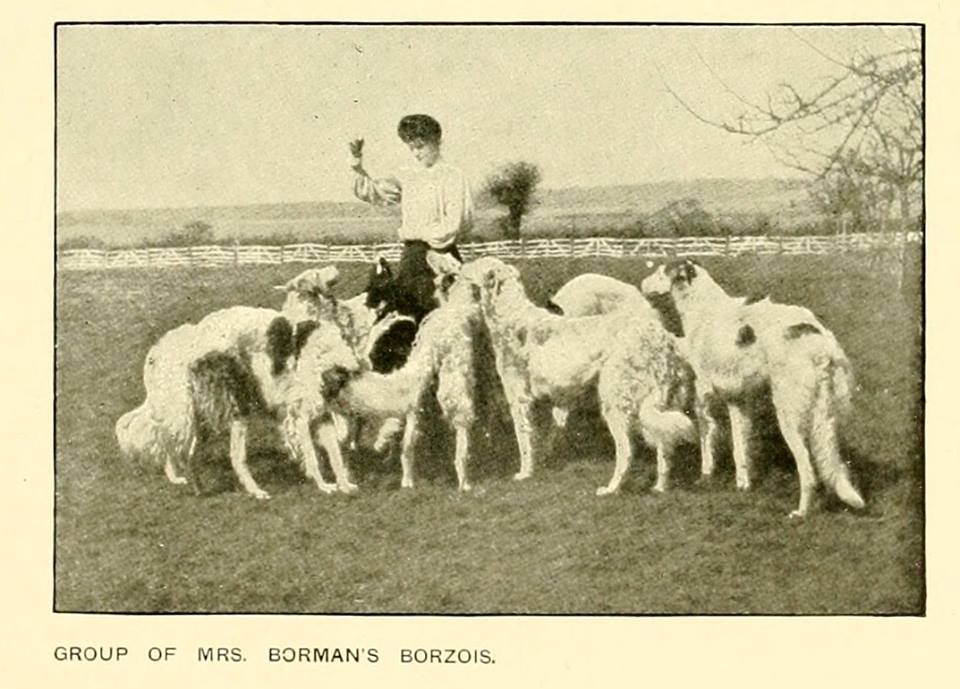

Bitches – Chs. Sunbeam, Theodora, and Tatiana - Ramsden Kennels (Mrs. Borman’s):

Dogs – Chs. Kieff, Ramsden Ranger, and Statesman

Bitch – Miss Piostri - Padiham Kennels (Mr. Murphy’s):

Dog – Ch. Padiham Nordia - Mrs. Aitchison’s Kennels:

Dog – Ch. Strawberry King

Bitch – Ch. Votrio Vikhra - Mrs. May’s Kennel –

Dog – Ch. Berris

- Clumber Kennels (Her Grace the Duchess of Newcastle):

Now the photos here given, list of points, etc., should be an excellent guide to the intending Borzoi fancier; but it must be pointed out that the measurements apply to the best dogs of the past and present, and the novice must not expect quite such excellence unless prepared to open his purse-strings widely.

There are plenty of dogs living the measurements of which equal the above, but mere size is nothing unless quality is also present; and this is where the breeder’s difficulty arises – to get size without coarseness.

Assume that the reader has decided to start a kennel of Borzois. If one of Fortune’s favourites, and money is no object, the quickest way to reach the top of the tree is to purchase a full-blown champion, or at least a dog that has already made his name on the show bench. If this method does not appeal to him he has the choice of two other ways – either to buy a well-bred bitch and breed from her, or purchase a puppy. In either case, should he not understand the breed, he must not be led away by specious advertisements, but place himself in the hands of a breeder of repute – of whom there are many – and pay a fair price, and he will, in all probability, get fair value for his money. Especially does this advice hold good in the case of a young puppy (the purchase of which must always be more or less a lottery), for the following reason. Breeders cannot keep all their young stock, so that some must be sold, and a cast-off from a strain that has for years been carefully bred for certain points is far more likely to turn out a good dog than one the dam of which has been mated “haphazard.” Not only this, but the best kennels own the best bitches, and breed from them, and the dam is quite as important a factor as the sire. As regards price, a good puppy, when ready to leave the dam, should be had from £5 to £10, according to merit and parentage; one offered at a lesser price should be looked on with suspicion. Taking into consideration the value of the breeding stock, the risk to the dam, the cost of extra food, both for the dam while in whelp and the pups in the nest – for pups are, or should be, fed from three weeks of age – it stands to reason that no breeder can afford to sell a promising puppy under the figure mentioned.

As regards choosing a puppy, the writer would always recommend the intending purchaser, when feasible, to go and see the whole litter. He can then compare the pup with its brethren as regards head, bone, coat and other points, and the puppy will be seen to better advantage than if hauled out of a box or hamper after a long journey, to find itself amidst strange faces and surroundings.

Length of head, well filled up before the eyes, big bone, small ears, dark eyes and straight legs are the points to be chiefly looked for, or as many of these qualities as can be found combined in one individual. A long tail usually indicates ultimate large size. Coat is a minor matter; if both parents possess good coats the pups will, in all probability, inherit. If the parents fail in coat, then, no matter how good the “puppy coat,” once this is cast, the adult coat will most likely be poor.

Having got the puppy home, the first question is accomodation. It may be brought up indoors, or in a loose-box (which makes a capital puppy house), or it may be kept in a kennel with a railed-in run. Never chain up a Borzoi pup – or even an adult dog – if it can possibly be helped; not only is it cruelty, but the puppy would soon be ruined. If, therefore, you cannot allow the pup full liberty, at least during the day, the best thing to do is to try another breed.

The next question is food. A puppy up to four months old should be fed five or six times a day; lean meat minced fine, raw or cooked, stale bread and rice are suitable – in fact the greater the variety the better. At five months the number of feeds may be reduced, until, at six months, only three are necessary. Milk is most valuable, and should be given freely. At about four or five months of age, the puppy must be taught to go on a collar and lead.

Borzoi pups are a mass of nerves, and require very gentle treatment. If you can persuade the pupil that the collar and lead are merely accessories to a good game, probably he will take to them immediately, but once frighten him, and it requires hours of patient labour to induce him to follow.

The pups should be dosed for internal parasites when about eight weeks old, for which purpose the writer has found no worm medicine to equal “Ruby.” It can be safely given to Borzoi pups of seven weeks if necessary; in fact, all the writer’s puppies are dosed at that age, and he has never known “Ruby” to cause any ill effects.

As regards the height of puppies, the average height only can be given, and may be exceeded in some cases, or the contrary.

Three months old, 19 in. at shoulder,

Six months old, 25 in. at shoulder,

Nine months old, 27 to 29 in.

After nine months the growth is, as a rule, slow, continuing in some instances to 18 months. A Borzoi continues to fill out in girth, etc., up to two years, and may be considered in its prime at three to four years of age.

Borzois, as a rule, make excellent mothers, experiencing little difficulty in whelping. The litters vary from two to a dozen or more, but five pups are enough for the average bitch to rear; six may be allowed if she is a big, strong bitch. It is better to consign the remainder to the bucket, or to procure a foster-mother if the litter is very valuable. The first few weeks of a puppy’s life are all important, and it is wiser, by far, to sacrifice two or three pups for the benefit of the remainder, which thereby get a greater share of the dam’s milk. At the age of three weeks the puppies should be taught to lap, thus avoiding too great a strain on the dam’s system.

With regard to the all-important question of the sire, the writer would impress on the would-be breeder the maxim that “like breeds like,” and if you want to breed high-class stock you must use the best material available. Breeding from inferior dogs in order to save a sovereign or two on the stud fee is economy of the worst description. Fourth-rate pups cost as much to rear in time, trouble and food as first-rate ones; and when reared there is no sale for them: whereas pups by a well-known dog will always command a market. For the same reason breeding from a really inferior bitch is not to be recommended, because, however good the stud dog, he cannot counteract any excessively bad faults. Still, a bitch of good pedigree, perhaps not quite up to show form, can often be purchased for from £10 to £15 and even less, and mated to the best dog, the pedigree of which is suitable, should ensure a litter of likely winners.

Borzois, whether pups or adults, require only the same treatment as other large breeds. They can stand a great amount of cold, provided their quarters are dry; in fact, the colder the weather the more they seem to enjoy it. The writer’s hounds are kept in cold kennels, with open doors, the whole year round. Damp, of course, must be avoided. Rugs are unnecessary for this breed, except, perhaps, when travelling at night in winter, after leaving a show, where the building has been heated.

With regard to the preparation for showing, a Borzoi should be brushed regularly and the feathering combed out to prevent it matting. If this is done no further preparation for exhibition will be required, except a bath a day or two previous to the show. Rain-water, if procurable, tends to soften the coat – a little liquid ammonia in the water helps to remove dirt and grease. Borzois should not be shown too fat, as it spoils their symmetry of outline. It is one of the great advantages of the breed that the novice can show on equal terms with the old hand, without having first to serve a long apprenticeship in “trimming.” Keep your dog in good, hard condition, and show him clean – no one can do more.

The interests of the breed are well looked after by the Borzoi Club. It was founded on March 29th, 1892, with the Duke and Duchess of Newcastle as joint Presidents, by some dozen or so ardent fanciers of the breed, many of whose names are household words in the canine world, including G. R. Krehl, Sir Everett Millais – then Mr. Millais – Freeman Lloyd, W. E. Allcock, Colonel North and W. R. Hood Wright. At the present time the club consists of some 70 members, from whom a committee of 12 is elected annually. The income of the club is entirely devoted to guaranteeing classes and to offering medals and cash specials for competition among its members. The Hon. Secretary will at times be pleased to furnish full particulars to any lady or gentlman desirous of joining.*

Taken as a whole, it can safely be said that the breed has made good progress towards the desired type – as exemplified by Boldareff’s Russian team – in recent years. Fewer of the apple-headed specimens, with pronounced stop, are seen, and more of the “triangular” heads. The writer fears we are, to some extent, losing the former beautiful, silky texture of coat; and quantity is by some sacrificed to size. He has also noticed a tendency, in trying to improve the feet, to run to the other extreme, and breed the Borzoi “cat-footed.” However, Rome was not built in a day, and the writer can only suggest that, with the above-mentioned team for a model, breeders should “peg away” until they produce the perfect – or almost perfect – Borzoi.

*Originally 28 and 26 ins.; altered at the general meeting of the club, February 1905. The Russian Wolfhound Club of America gives the following definition of height, which is, in the writer’s opinion, preferable. Dogs, average height at shoulder, from 28 to 31 ins. Larger dogs are often seen, extra size being no disadvantage when not acquired at the expense of symmetry, speed and staying power.

*Hon. Sec., Major Borman, Ramsden, Billericay, Essex

Photos added by Dan Persson

Year of Event:

Country:

Personal Collections:

Source:

Author:

Dogs:

Persons: