The Borzoi Or Russian Wolfhound (from the book “”A History And Description Of The Modern Dogs Of Great Britain And Ireland. (Sporting Division)”, by Rawdon Briggs Lee”)

There is no dog of modern times that has so rapidly attained a certain degree of popularity as that which is named at the head of this chapter. A dozen years ago it was comparatively unknown in England; now all well-regulated and comprehensive dog shows give a class or classes for him, which are usually well filled, and cause quite as much interest as those for our own varieties. Indeed, the Borzoi is a noble hound, powerful and muscular in appearance, still possessing a pleasant and sweet expression, that tells how kindly his nature is. He is one of the aristocratic varieties of the canine race, and the British public is to be congratulated on its discernment in annexing him from the Russian kennels, where, too, his reputation is of the highest.

In the early days of our dog shows, Borzois, then known as Siberian and Russian wolfhounds, and by other names, too, occasionally appeared on the benches. Most of them were similar in type to those we see now, and no doubt have a common origin with the ordinary Eastern or Circassian greyhounds, occasionally met with in this country. But the latter were usually smaller and less powerful than their Russian relative. According to the “Kennel Club Stud Book’ a class for “Russian deerhounds” was provided at the National dog show held at the Crystal Palace in 1871. This was not the case, but a foreign variety class was composed almost entirely of Russian hounds, and one of them, Mr. S. T. Holland’s Tom won the first prize. Lady Emily Peel and Mr. Macdona were exhibitors at the same show.

It will be nearly thirty years since the Czar of Russia presented the Prince of Wales with a couple of his favourite hounds, Molodetz and Owdalzka. These his Royal Highness exhibited on more than one occasion, and bred from them likewise, Mr. Macdona having presented to him one of the puppies. History repeated itself when in 1895 H.R.H. the Princess of Wales was presented with a splendid hound called Alex, from the Czar’s kennels, which has met with a considerable amount of success at several leading shows. In 1872 Mr. Taprell Holland showed an excellent hound in the variety class at Birmingham, for which he obtained a prize. Even before this, specimens of the Borzoi (sometimes called Siberian Wolfhounds) were met with on the benches at Curzon Hall. In 1867, Mr. J. Wright, of Derby, had one called Nijni; and three years later the same exhibitor benched an excellent example of the race in Cossack, a grandson of Molodetz, already mentioned as having belonged to the Prince of Wales, and being from the Imperial kennels. Perhaps the earliest appearance of all on the bench was in 1863, when the then Duchess of Manchester showed a very big dog of the variety at Islington, and bred by Prince William of Prussia. I have the authority of Captain G. A. Graham for stating that this hound was 31 inches at the shoulders, quite equal in size, as he was in power, to some of the best specimens now on our shores.

Thus, after all, this fine race of dog is not quite such a modern institution in our country as would be imagined, though the earlier strains, I fancy, must have been lost, possibly on account of the inter-breeding consequent on an inability to obtain a change of blood. Communication between the eastern and western divisions of Europe is now much more rapid and easier of accomplishment than in the early days of dog shows.

Advancing a few years, Lady Charles Kerr occasionally sent some of these Russian hounds to the exhibitions, but most of them were small and somewhat light and weedy – far from such powerful animals as the best that are with us to-day, and even they in height do not reach that which belonged to the late Duchess of Manchester, and already alluded to. Of course, long before this, the dog, in all his prime and power, was to be found in most kennels of the Russian nobles. Some of them had strains of their own, treasured in their families for years. Such were mostly used for wolf-hunting, sometimes for the fox and deer, and bred with sufficient strength and speed to cope with the wolf – not, indeed, to worry him and kill him, but, as a rule, to seize and hold him until the hunters came up.

In 1884 a couple of Borzois, which even then we only knew as Russian wolfhounds, were performing on a music-hall stage in London, in company with a leash of Great Danes. The latter were, however, the cleverer “canine artistes,” though the former the handsomer and more popular animals. I fancy their disposition is too sedate to make them eminent on the boards, resembling that of the St. Bernard and ordinary Highland deerhound, neither of which we have yet seen attempting to emulate the deeds of trained poodles and terriers in turning somersaults and going backwards up a ladder.

A correspondent, writing to the Field in 1887, gives the following description of the Borzoi, and it is so applicable to him at the present time as to be worth reproducing here. He says this Russian hound “Is one of the noblest of all dogs, and in his own land he is considered the very noblest, and valued accordingly. Like all things noble that are genuine, he is rare; and, like many other highly-bred creatures, the genuine Borzoi is, from in-breeding, becoming rarer every year. By crossing, however, with the deerhound and other suitable breeds, the race will no doubt be kept alive with stained lineage.

“From the earliest times, the great families of Russia have bred the Borzoi jealously against each other for the purpose of wolf hunting, but there are now few really good kennels of the breed. There are, I believe, various kinds of Borzois – the smooth, the short-tailed, etc. – but by far the handsomest, and the only one of which I have personal knowledge, is the rough-haired, long-tailed strain. Of these I have seen but very few good specimens in England, and, in fact, have seen prizes given at shows to very inferior specimens entered in the foreign class under his name. The true Borzoi is shaped like a Scotch deerhound, but is a much more powerful dog. In height he should be from 26m to 32m., with limbs showing great strength, combined with terrific speed power. Indeed, their speed is greater than that of an English greyhound. This quality is clearly shown by the long drooping quarters, hocks well let down close to the ground, and arched loins of such power and breadth as to give the dog almost a hunched appearance. The coat is silky, with a splendid frill round the neck, well-feathered legs, and a tail beautifully fringed on the under side. The carriage of the tail is peculiar, as it is almost tucked between the hind legs, so straight down does it hang until at the end it curls slightly outwards with a graceful sweep; but this, like the bang tail of the thoroughbred racehorse, adds to the beauty of the quarters. The depth of these dogs through the heart is quite extraordinary, giving them, with their enormous strength of loin, a very powerful appearance, and it seems strange that they do not possess more staying powers than they are generally accredited with. The head is very beautiful, being nearly smooth, and with immense length and strength of jaws, armed with teeth which make one feel glad to meet the Borzoi as a friend. The eyes are bright and wild, and have the peculiarity of varying in colour with the colour of the dog. Thus, a white dog marked, with lemon eyes; a mouse-coloured, eyes of the same tinge, and so on.

“The favourite colour of all, and. by far the rarest for these dogs, is pure white, but this is seldom met with. The usual colour is white, marked with fawn, lemon, red, or grey more or less mixed. Perhaps the prettiest features of all in the Borzoi are its ears, which are very small, fringed with delicate silky hair, and should be pricked with a half fall-over like a good collie’s. In his movements he much resembles a wild animal, and has quite the slouching walk and long sling trot which is a characteristic of his born enemy, the wolf. Yet to see a Borzoi trot out with his long swinging action, and then just break into a canter, has always reminded me of a two-year-old cantering down to the post. The muscles on the quarters, thighs, and arms should be well developed, as these dogs are intended, and in fact used, to course the wild wolf. Strong must be the muscles, long the teeth, and indomitable the pluck of the Borzoi, who has to encounter single-handed the wild Wolf in his own haunts. No doubt the Borzoi, on such occasions, remembers the well-known fact that the favourite meat of the wolf is dog, and acts accordingly. It is usual, however, to employ two Borzois to course a wolf, and it is only the best specimens that can be trusted to account for one single-handed.”

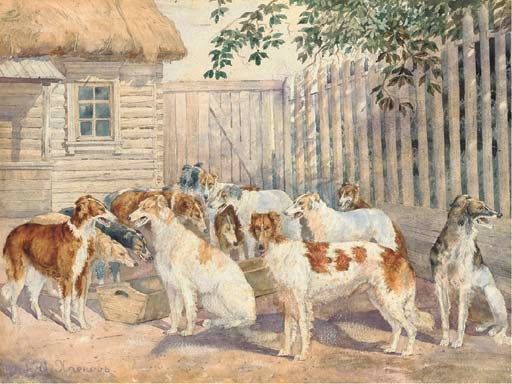

Perhaps, before going more fully into the Borzoi as a British dog, the following extract from an article by Mr. F. Lowe, who a few years ago spent some time in Russia, will give an idea of the extent of the kennels of the Borzoi hounds, and the value placed upon them in their native country. He says : ” In the south of Russia, from which I have just returned, I had the good fortune to be the guest of a keen and well-known sportsman, Mr. Kalmoutzky, who, since coming into the inheritance of a magnificent property of something like twenty square miles, has built kennels which I should say are not surpassed in any country – being very large in size, and as near to perfection in detail as can well be imagined. The lodging houses, numbering three, are benched on two sides, and at each end there is a room for a man; three kennelmen being allowed for each kennel, two of them on duty night and day. This gives nine kennelmen to the kennels and, with five other officials, the number of men employed on it are fourteen. It is necessary to have men in attendance at all times, as the wolfhounds are very quarrelsome, and terrible fighters. Each kennel has a large yard of more than three-quarters of an acre. In addition to the above, there are commodious kennels for puppies (and these buildings are heated with hot air), cooking houses, and a hospital. There is telephone communication from all the kennels to Mr. Kalmoutzky’s house, and he expects everything to be in readiness for a hunt in ten minutes from the time he sends his orders.

“In the kennels above described can be seen perhaps the finest pack of wolfhounds in the world, numbering twenty-two couples. They form a magnificent collection, their owner having spared no expense in getting the best to be found in Russia, and of the oldest blood. Some of them have cost £300 each; and the estimated worth of the pack is considerably over £5000.

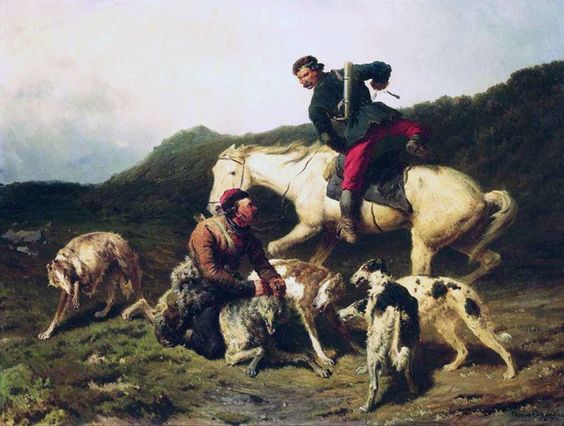

“A perfect wolfhound must run up to a wolf, collar him by the neck just under the ear, and, with the two animals rolling over, the hound must never lose his hold, or the wolf would turn round and snap him through the leg. Three of these hounds hold the biggest wolf powerless; so that the men can dismount from their horses and muzzle the wolf to take him alive.

“The biggest Scotch deerhounds have been tried, but found wanting; they will not hold long enough. And to show how tenacious is the grip of the Russian hounds, they are sometimes suffocated by the very effort of holding. Some of them stand 32in at the shoulder, are enormously deep through the girth, and their length and power of jaw are something remarkable. They have a roach back, very long, muscular quarters, and capital legs and feet. In coat they are very profuse, of a soft, silky texture, but somewhat open.

“I took the journey to Russia with eleven couples of foxhounds, as additions for Mr. Kalmoutzky’s pack. I had cases made to hold two hounds, so that I had eleven of these big packages, which went as my personal luggage, the weight being a ton and a quarter. It took me exactly seven days to get to my destination, from Dover via Paris, Vienna, and Jassy; and I was met in right regal state, as there was a carriage and four for myself, another for Mr. Kalmoutzky’s steward, and five waggons, each drawn by four horses, for the hounds, with seven chasseurs to take charge of them.

“We had nearly forty miles to drive; and the hardy little Russian horses did this at a hard gallop, over plains, with no roads, and there were no changes. We were just under four hours doing this wild journey; and my good friend and host, who did not expect me to arrive so early, had gone out on a wolf-seeking expedition; but on his return, the first thing, after a most hearty welcome, was to inspect the kennel, with which I was, of course, greatly delighted. He would not show me the wolfhounds at this moment, as that inspection was reserved until after dinner, when they were all brought into his study, one by one, and their exploits separately recorded. Noble looking fellows they are; and by their immense size and powerful frames, of much the same formation as our English greyhound, they are admirably adapted to course big game. They look quiet, but the least movement excites them; and in leading them even through the hall, from the study, there was very nearly a battle royal or two. The Russian chasseurs, though, beat any men I have ever seen in handling a hound; and their influence, apparently all by kindness, is extraordinary. I noticed that even the puppies at play made for the same spot in trying to pull each other down – namely, by the side of the neck under the ear; and this mode of attack seems instinctively born in them. The wolf’s running is perfectly straight, and if he attacks it is straight ahead; he will only turn if caught in a manner to do so; and a dog laying hold of him over the back or hind quarters would be terribly punished. The clever wolfhound never gets hurt, no matter whether he or the wolf attacks first; and some singular trials of this sort have taken place.

“Recently, a very big wolf, that had been captured with much difficulty, was matched against any two hounds in Russia. The challenge was accepted, and the wolf placed in a huge box in an open space.

The moment the trap was pulled the wolf stood and faced the spectators; on the hounds being slipped on him he attacked them; but they avoided his rush, and pinned him so cleverly that the wolf was muzzled and carried off without the least difficulty; whereupon an enormous price was paid for one of the hounds.

“The Russian style of hunting would not meet all our English views of sport; but there is doubtless a deal of excitement about it Mr. Kalmoutzky’s domain is entirely on a plain, with scarcely any woodlands at all. It is all like a “sea of grass,” the going being as good as on Newmarket Heath, with here and there the land turned up in cultivation, but looking much like patches in the vast expanse; so also did the reed beds of 300 or 400 acres each, and these are the coverts for the wolves and foxes. These reed beds are mostly eight or nine miles apart, so English foxhunters could see what a gallop could be had here; better than Dartmoor or Exmoor, as the turf is perfect, no rough ground, and the hills little more than undulations.

“Special hunts would have been arranged on my behalf, but, alas! like our own frozen-out sportsmen, I had to be disappointed, as frost and snow interfered. However, one morning I was given an insight into wolf coursing, by one that had been previously captured being let loose on the snow. First a very noted hound was slipped to show how one could perform single-handed. The start given to the wolf was about 200 yards, and in about 600 yards the hound had got up, and in the next instant had taken hold by the neck, and both seemed to turn head over heels in a mass. The next course two hounds were slipped, and these ran up to the wolf one on each side, catching him almost at the same moment; the foe was then powerless, and seemed to be as easily muzzled as a collie dog.

“I remarked to my host that I did not think the hounds seemed to go quite as fast as our greyhounds, and he replied, ‘No, they do not. We have tried them, and the greyhound is the faster; but none of your breeds have the hold of our hounds.’

“The plan of a regular hunt was fully described to me. It is decided to draw a reed bed, and very quietly a mounted chasseur with three wolfhounds is stationed on some vantage ground near. Other points are guarded in the same manner, and then the head huntsman rides into the covert with a pack of foxhounds. The oldest wolves will break covert at almost the first cheer given to hounds; but the younger ones want a lot of rattling. However, the keen eyes of the men and hounds soon detect wolves stealing away; the three hounds are then slipped, a gallop begins, and generally, in the course of a mile or less, the wolf is bowled over. The chasseur then dismounts, cleverly gets astride the wolf, and collars him by the ears, the hounds still holding on like grim death. Another chasseur rides up, slips a muzzle on the wolf, which is then hauled on to one of the horses, tightly strapped to the Mexican sort of saddle, and taken off to a waggon in waiting near. Foxes are similarly coursed and killed with foxhounds, the latter being stopped at the edge of the covert.”

The following account of a wolf hunt, from the pen of an English officer, will perhaps be found interesting, as it deals with one or two matters not alluded to by Mr. Lowe:

“Some years ago, while I was in the Russian service, the officers of a cuirassier regiment gave ‘ours’ a chance to see these fine dogs work. We had been trying to hunt wolves with our pack of boarhounds, but with little success. Occasionally we shot one, but, though our dogs could bring the biggest boar to bay, they were useless in tackling wolves. Several of the boldest and fiercest hounds had been crippled by the savage brutes.

“One day a courier rode over with an invitation for all of us to go to Bielowicz two days later. The Czar’s wolfhounds were expected to arrive at the lodge at that date, and fine sport was promised. ‘Don’t trouble to bring any weapons,’ the letter ran, ‘for these are the dogs we have told you so much about, and they are to do all the work.

“Of course we all clamoured to be allowed to go, and gained our point with our good-natured colonel. As there were fifteen of us then on duty, it was arranged that three parties of five should each take three days off, for it took two days to go there and back. My party got off first, and by riding all day we reached the lodge before night. The cuirassiers gave us the best of welcomes and a fine dinner, to which the chasseur en chef was also invited. The gentleman had for twenty years had charge of the Czar’s wolfhounds.

“After dinner he ordered his men to bring in some of the best dogs for our inspection. An attendant dragged them in one at a time, not without some trouble; but as soon as they saw the chasseur they became as quiet as lambs, and did anything he ordered. He was very proud of them, and gave us interesting details of their prowess. One huge fellow, called Dimitri, had the repute of being able to catch and hold the largest wolf single-handed, and the chasseur promised to show him off to us the next day.

“As the coverts to be drawn were seven miles away, we took an early start. Twelve chasseurs, each leading a fine wolfhound, rode in advance; four attendants, with a pack of common hounds, followed. Next came a big iron cage drawn by four horses, in which the captured wolves were to be put; for, while small and inferior wolves are killed, all the largest are kept for the young wolfhounds to practise upon.

“As soon as the common hounds were sent into the underbush, hares and foxes came rushing out, but the boars and wolves were harder to start. The chasseurs had taken up good positions along the edge of the forest, where a stretch of open plain offered a splendid chance to see the fun if any wolves were driven out. I kept with the man who had charge of Dimitri.

“With ears erect and nose in the air, this fine dog seemed to take as much interest in the sport as any of us. Though the barking and baying hounds in the coverts came nearer every second, he never moved a muscle nor made a sound. Suddenly a big, black wolf rushed out of the scrub, gave one glance around, then started off for the next covert a mile away.

“All the dogs tugged at their leashes; but not till the wolf had a clear start of two hundred yards did the head chasseur’s bugle ring out. It was Dimitri’s call; and as he was loosed, he gave one fierce howl and then bounded silently away.

“With such tremendous energy did he start that his feet hardly seemed to touch the ground. Every leap seemed longer than the last; and as he grew smaller in the distance, he looked like a big rubber ball bouncing over the plain. In less than a minute he had overtaken the wolf and seized him by the neck under the right ear. A cloud of dust flew up as dog and wolf rolled over and over; but when it cleared away, we saw that Dimitri had brought the beast to a standstill. His chasseur had followed him as quickly as his horse would run. On coming up the man jumped down, and, getting astride of the wolf, fastened a strong muzzle over its jaws, secured a chain round round its neck and dragged the now skulking animal back to where the cage stood.

“In the meantime other wolves had been started, and several of the dogs were hard at work. When two were loosed in pursuit of one wolf, they ran alongside of him, one on each side, until a favourable opportunity offered, when, with a sudden snap, one would seize the creature. As the wolf turned to try to free himself, the other would get a grip that prevented him from moving at all.

“So surely and neatly did these dogs do their work that not one was bitten, although no animals can do quicker or more damaging work with their jaws than wolves.

“Seven wolves were driven out of that covert, but only two were thought to be worth keeping. They were put in the cage, and we moved on to the next likely spot. In the course of the day the dogs caught sixteen wolves, not one got away when fairly out of cover, and we returned to the lodge with five fine live wolves.

“While discussing the ways of wolves that evening after dinner, one of us ventured to express a doubt whether even Dimitri could successfully face a wolf at bay. The speaker was satisfied that the dog could seize and hold a running wolf, but did not believe he could avoid the savage attack such an animal makes when cornered. Before we left next morning he was convinced of his error. The largest captured wolf was turned loose in an inclosed yard, and Dimitri was set on him. Seeing himself trapped, the wolf did not wait for the dog to attack, but rushed straight at him.

“The two animals met and closed, rolling over and over; but when the struggles ceased, Dimitri had the wolf securely by the neck, and had not received a scratch. Our friend, the chasseur en chef, offered to bring out other hounds that could do this feat as well as Dimitri; but we were convinced.

As our time was up, we departed, regretting that we could not take a few of the Czar’s wolfhounds away with us.”

Following the publication of Mr. Lowe’s article some correspondence ensued, and Colonel Wellesley forwarded an interesting communication he had received from Prince Obolensky on the subject. His Royal Highness, who has a famous strain of Borzoi of his own, and may be taken as a leading authority on the breed, says :

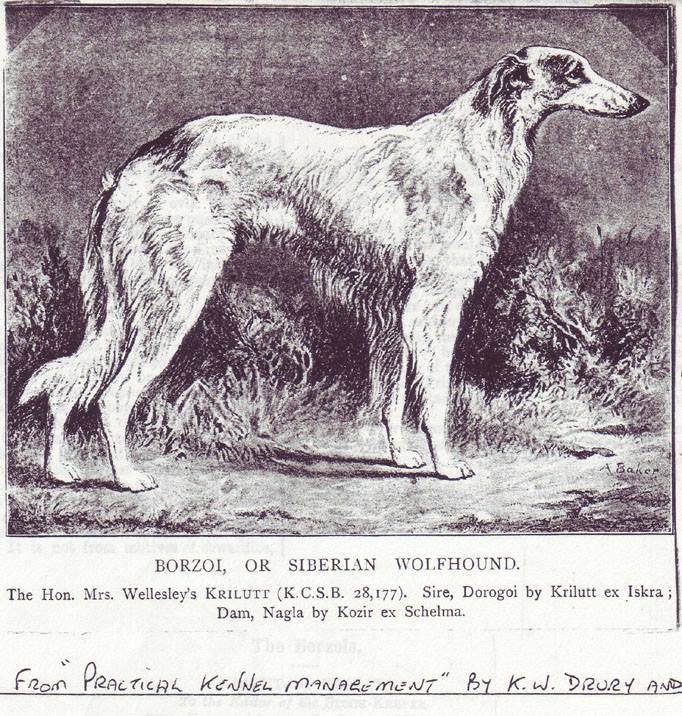

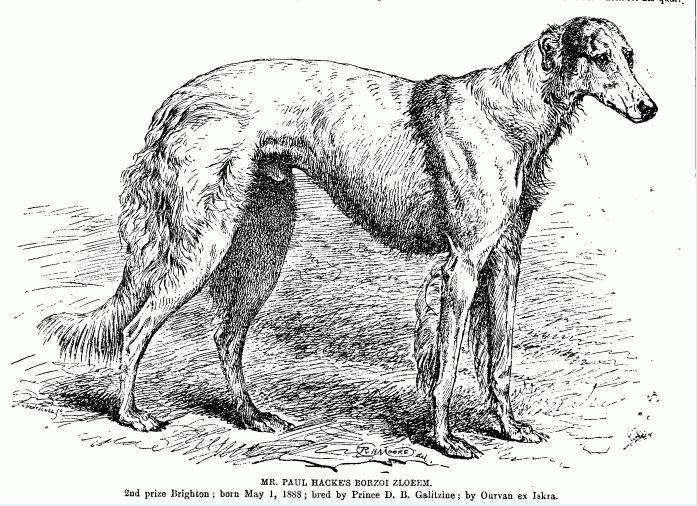

“The dogs that have been catalogued at various shows in England for the last three years are pure Borzoi, and have come originally from the best kennels in Russia. For instance, Krilutt, Pagooba, Sobol, Zloeem, and others were not ordinary working hounds, but dogs that were admired in their native country, both on the show bench and in the field. Pagooba, for example, who is of exceptional size for a bitch, has several times pinned wolves single-handed.

“The English traveller mentions the size – viz., 32m. – of the dogs he saw as tremendous. There are exceptional cases where the Borzoi has stood very near that height. At the dog show in Moscow this year a dog called Pilai measured 31½ in., or 80 centimetres; but the average height is from 28m. to 29½ in. It often proves to be the case, however, that, for working purposes, the smaller dog shows itself to excel in speed, pluck, and tenacity.

“For wolf hunting I personally prefer the English greyhound, acclimatised here (i.e. born in Russia from English parents); but I am also a great admirer of the Russian rough-coated Borzoi. I may claim to know something about the latter, because for many years I have bred and hunted them, and my dogs are the lineal descendants of those bred by my grandfather, General Bibikoff, who was himself renowned for his sporting proclivities, and for the excellence of his breed of dogs. So valued is that strain now, that it can be found in most of the best kennels in Russia.”

In addition to sport with Borzois obtained in the above manner, occasional meetings are held where hares are coursed; and “bagged,” or rather “caged,” wolves treated in a similar manner. Judging, however, from what I have been told of such gatherings, they are by no means desirable or of a high class, so need not be further alluded to here.

It is but natural that with the popularisation of a new variety of dogs, some discussion should take place thereon. In the present instance, an attempt was made upon the name of the hound, but as the word Borzoi had obtained general acceptance, was easy to pronounce, and not too long to puzzle even a child, the “raid” failed. It is now adopted by the Kennel Club, by the chief Russian authorities, and no doubt that hound once known as the Russian wolfhound will remain the Borzoi to the end of his days. On this matter, Prince Obolensky says: “I am glad to see English sporting papers adopting the Russian name for this breed, for the word itself (Borzoi mas., Borzaia fem.) means ‘swift and hot-tempered;’ and though poets sometimes apply the expression to a high-spirited steed, it is, with this exception, always applied to greyhounds only; for this reason the English greyhound is called, in Russia, ‘Angliskaia Borzaia,’ or English Borzoi.”

Some little time before the above was published, Lieutenant G. Tamooski, writing from Merv, proposed the term “Psovi,” which means literally “thick coated,” as a fit name for the dog as it is known in this country, because he says “Borzoi” means any coursing hound whatever.

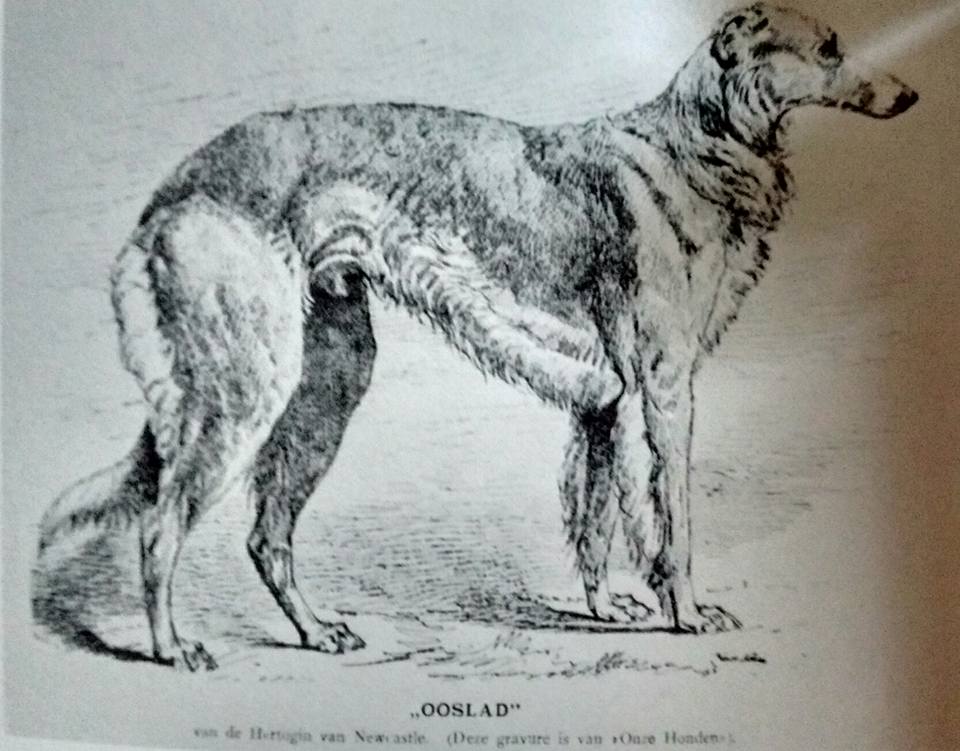

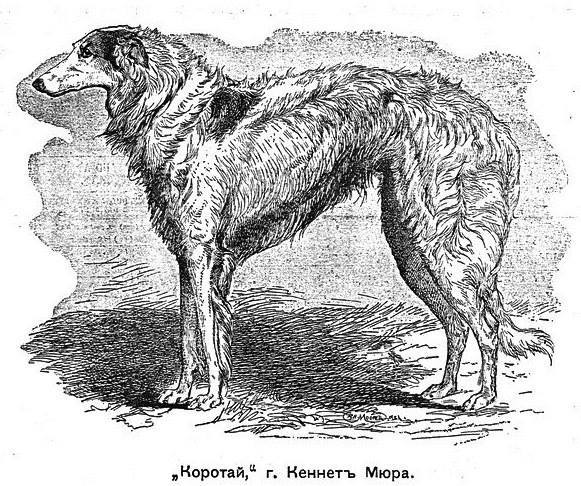

The Duchess of Newcastle, Colonel and the Hon. Mrs. Wellesley, the Duke and Duchess of Wellington, Mrs Morrison, of near Salisbury; Lady Innes Kerr, Mr. A. H. Blees, Mrs. Coop, Mrs. W. B. Stamp, Mrs. E. H. Barthropp. Mrs. M. E. Musgrave, Mrs. G. W. Fitzwilliam, Miss A. M. Head, Mrs. Young, Miss M. Thompson, and many others, have given particular attention to the Borzoi, and they, with Mr. K. Muir, an English resident in Moscow, who brought over with him, during a visit to this country, a couple of excellent hounds, own, or have owned, animals perhaps as good as can be found in any Russian kennel. Their best specimens are much stronger, and more powerful than most of those seen at our earlier shows. Mrs. Wellesley’s Krilutt was measured to be 30m. at the shoulders, and pretty nearly 100lb. in weight, and Mr. Muir’s Korotai was half an inch taller, and said to be 110lb. in weight. Both were Russian born, and proved their ability to win prizes at St. Petersburg and Moscow, as well as in our own country. Like the rest of their race, they are “thick coated dogs” – the smoother ones are not liked in this country – not so hard in their hair as the English deerhound, but the jacket is closer, and, if not so straight, is perhaps the more weather-resisting of the two. As the Russians themselves say that the two kinds of coat, thick and comparatively smooth, appear in puppies of the same litter, there is no other conclusion to arrive at, that they are one and the same variety. At any rate, they are allowed to be so in this the land of their adoption.

Considerable interest was taken in the extraordinary collection of this hound that appeared at the Agricultural Hall, Islington, in February, 1892.

Here, many classes had been provided, the result being an entry of about fifty. These included a splendid team from the “Imperial Kennels,” most of which belonged to the Grand Duke Nicholas. However, three were actually the property of the Czar, including a beautiful bitch called Lasca, and a couple of dogs, Oudar and Blitsay. Oudar was a particularly fine hound, and though in bad condition, consequent on his long journey from St. Petersburg, he stood well with the best of our previously imported dogs, and in the end gained second honours in perhaps as good an open class as was ever seen anywhere. He stood 30½in. at the shoulders, and scaled about 1051b.

Most of these Russian dogs were sold, some of them for high prices, Oudar realising £200, the bitch already named as much, and the then Lord Mayor of London was presented with a handsome specimen. Their “caretaker” had instructions to sell the lot, but none for less than £20 apiece. The strains in this country have been improved by these importations, and any fears as to degeneracy from inter-breeding may now be set at rest. Another big dog of the race was Colonel Wellesley’s Damon, 30¾in. at the shoulders, and about 110lb. in weight, but when we saw him he did not quite equal in symmetry and general excellence such dogs as Krilutt, Oudar, Korotai, and may be of another dog, imported by Mr. Summerson, of Darlington, called Koat, afterward H’Vat.

To dwell a little more upon the very best specimens seen in England – Krilutt and Korotai, with Oudar and Ooslad, have been and still are equal to anything I have seen. The latter, a fawn hound, is rather smaller than the others, but on one occasion, at least, he beat Korotai, a decision with which I did not agree; for if Ooslad was a little finer in the head, his opponent beat him in coat, colour, power, size, and in all other particulars. Korotai was a white dog with slight blue markings. It is said that when in Russia he had run down and overpowered a wolf. His strain was of the highest and most valued pedigree, and I certainly liked him the best of any of his race I had seen until Oudar came on to the scene. However, at the show already alluded to, the latter was not in good condition, and suffered defeat; Korotai winning chief honours in an extraordinary fine lot of dogs. Krilutt had been in the challenge class; Oudar was first in a division for novices, and at the present time he is well cared for in the kennels of The Duchess of Newcastle at Clumber, and, although now over eight years old, is able to take more than his part against the best on the show bench. At the present time there are over fifty Borzois at Clumber, of which Velasquez and Velsk, by Korotai – Vikhra, are perhaps the best couple ever bred in this country. Tsaritsa, bred by Count Stroganoff, also deserves special mention, a bitch by many good judges considered the best of her sex ever exhibited.

(Mr. O. H. Blees’s), a black and tan in colour, was also a very nice hound, excepting so far as the colour goes, which is not good. The owner of the last named Borzoi, who is a Russian, has repeatedly been an exhibitor in this country, and at the Kennel Club’s show, in 1891, he took first, second, and third prizes in dogs, but was not so successful in bitches, where Mr. F. Lowe won, with a powerful and excellent specimen he had brought with him from Russia, and called Roussalka. She would, no doubt, have been useful here, but, unfortunately, died soon after the show. Colonel Wellesley’s bitch, Pagooba, and Mr. R. B. Summerson’s dog Koat, afterwards H’Vat, were hounds of high class.

Of these many excellent specimens, Colonel Wellesley must have the honour of being first in the field with Krilutt, who made an early appearance – and a most successful one it was – at the Kennel Club show, when held at the Alexandra Palace in 1889 – the year of the bloodhound trials. Krilutt had come with a great reputation as the winner of a silver medal at Moscow, and quite bore out all the good words that had been said of him. Exquisite in coat and colour – the latter white with light markings of pale fawn – he stood taller than any other dog in his class, and up to this period and for some time after was certainly the best Borzoi I had seen. Since, two or three have appeared that are, I believe, quite his equals. Whether it is worth while mentioning a dog named Zloeem, which, a year later, had been purchased in Russia by an American gentleman, Mr. Paul Hacke, is an open question. However, it was said that Zloeem could lower the colours of Krilutt and all other opponents, and at Brighton and the Crystal Palace was produced for the purpose of doing so. How completely he failed is now a matter of history – a second-rate dog only when at his very best. Since the above dogs flourished many good specimens have appeared, notably H.R.H. the Princess of Wales’s Alex, who has been particularly successful on the bench; Mrs. Coop’s Windle Courtier, the Duchess of Newcastle’s Velasquez, Vikra, and Milkha; Mrs. Kate Sutton’s Vera III., Mrs. Barthropp’s Leiba, Mrs. Musgrave’s Opromiot, Mrs. Stamp’s Najada, and some others, the names of which do not occur to me.

It might be well to mention that considerable risk is run by the loss of these dogs immediately after their arrival in this country. To my personal knowledge, three or four deaths have so taken place. No doubt the changes of food, in their manner of living, and in other surroundings, bring on a complication of disorders not unlike ordinary distemper. That handsome bitch, Rous-salka, brought over by Mr. F. Lowe, died soon after it left his kennels – it cost its new owner £100; and Mr Muir’s Korotai had a narrow escape, lying at death’s door for several days. Being a dog of strong, hardy constitution, and well nursed, he contrived to pull through.

The usual colours of the Borzoi are white with markings of fawn in varying shades, of blue or slate, sometimes of black and tan. The latter is not considered good, nor are the whole colours which are occasionally seen – fawn and black and tan. Some of the white dogs are occasionally patched with pale brindle, which, however, is not so well defined in its bars or shades as that colour is found on our greyhounds and bull dogs. Many persons object to the brindle or “tiger-coloured” marks, and Colonel Tchebeshoff, one of the great authorities on the breed, disqualifies black, and black and tan, and white with black spots, as indicating descent from English or Oriental greyhounds. Still, against this opinion there is a famous picture, in the possession of the Czar, of four Borzois chasing a wolf. At least one of these animals has the appearance of being black and tan, with an almost white face, very broad white collar and chest, white stern and hind quarters.

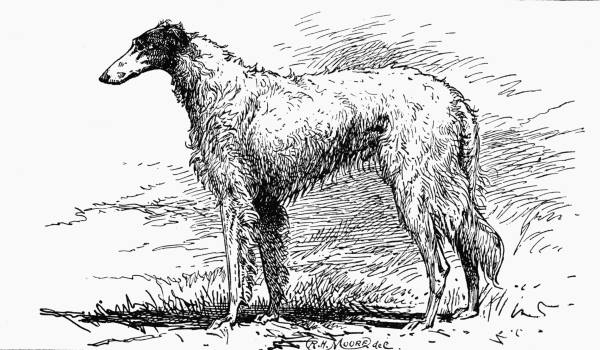

The size of the Borzoi and his coat will have been surmised from what has already been written. His general appearance will be seen from the illustration. As a companion he is highly spoken of, but, like all other dogs, he must be brought up for the purpose for which he is intended. In most of the Russian kennels he is kept solely for hunting a savage animal (by a few only to be used for fox and hare), and to do so successfully must be savage himself. Those which have been reared in this manner, and not had the benefit of civilising home influences, are not to be trusted any more than would one of our own foxhounds. But, as I have said, properly brought up and educated, he will be found as companionable as the best – no fonder of fighting than the deerhound, faithful as the collie, and as handsome and picturesque as either. His naturalisation with us is accomplished, and I can see no reason whatever why he is any more likely to be eliminated from “Modern Dogs” than the St. Bernard. He will be used here as a purely fancy variety; there are no wolves for him to kill, hares and rabbits are out of his line, and deer must be left for the big foxhound and the Highland deerhound.

I have written of the Borzoi as we know him here, and as he will in the future be known, taking no account of the various strains said to be in the Czar’s dominions, and the following description of him, translated from the Russian by M. A. Boldareff, a member of the Imperial Hunt, Moscow, and which appeared in the Stock Keeper in July, 1896, will be found interesting : (The Boldareff family was also owner of the Woronzowa Hunt and Artem Boldareff, together with the Cheremeteff brothers wrote the first FCI Breed standard 1924.)

“The general appearance of the Borzoi is noble and elegant. This is shown in the shape of the head, the silkiness and brilliancy of the hair, and even in the gait, which should be full of energy and grace. The different points of the dog, taken separately, have no value in the general appearance; the dog may have defects in head properties, in the body, in the legs, the coat may be too short, but nevertheless its air of nobility and elegance, its blue-blood aspect, will indicate purity of breeding. Only pure blood and careful breeding for several generations will impart this look, which excites the admiration of connoisseurs of Borzois and all other lovers of dogs.

“It is a pity that nowadays many of our sportsmen surrender general appearance for perfection in other points, so that the Borzoi of high and noble quality is becoming rare.

“The pure race of the Borzoi is principally characterised by the shape of the head, the ear, and by the tail. Many breeders concentrate their attention upon the head, and disdain the tail.

“We find, on the contrary, that the tail is one of the most characteristic points of race, because its thinness, its elasticity, and its shape, which resembles a reaping hook (a), among all the Russian breeds (we consider the Crimean and Caucasian varieties as Russian) belong exclusively to the Borzoi (b).

“Muzzle slightly arched and forehead prominent are typical of the Borzoi, but when the arch is too pronounced or the forehead too prominent, they are faults.

“The skull must be long, oval to the sides, and have a small slip to the back part of the head, finishing by a prominency sharp enough and well pronounced. Every other form is not typical.

“The muzzle is long, thin, and clean, the nostrils rather large and slightly projecting over the lower jaw. The nose must be black (a).

(a) A comparison very popular among Eussian hunters.

(b) The writer forgets the greyhounds of Poland, whose tails are exactly of the same shape as the Borzoi, only covered with very short hair.

“The eye must be full, and of oblong shape (an oblique eye is a defect, and a round one is not typical); it must be of a dark colour in a dark lining (b). Its expression is austere, but certainly not when indoors or when the dog is caressed, but at liberty or while hunting.

“The ear is small, thin (its thinness is a proof of high blood), having the form of a wedge. It must be very mobile, and is sometimes carried erect like a horse’s ear (c).

“This last quality is one of the best proofs of high birth. The hair that covers the ear must be very short, soft as satin, and must not grow in bunches. The dog should carry its neck like an English greyhound, but the Borzoi’s neck is shorter, and is not so straight. The shoulders should be flat and well seen; the elbows must not be turned outwards, but should be clear of the sides of the dog.

“The arch of the back of a dog must be quite regular and make no impression of a hump. The arch seems higher than it really is, because the hind part of the dog is higher than the fore part. The bitch has the back less arched, but even a high arch must not be considered as a great defect.

(a) A nose not sufficiently black, even when it has the colour of flesh, must not be considered as a proof of bad race. It is simply a symptom of poorness of blood.

(b) A light eye and the absence of a dark lining represent the same defect as a light nose.

(c) A favourite comparison with Russian amateurs.

“The ribs of the Borzoi must descend as low as the elbow They can be either flat or round, their form depending upon the breadth of the back; but they must never be too round (a). The ribs must gradually get smaller to the stomach. The stomach is drawn in and quite hidden behind’ the groin. The groin of a dog must be small; the less the better. A bitch must have it longer.

“The hind quarters are long and broad. The dog is more sloping than the bitch. A short and drooping loin is a great defect, because it forces the hind legs to be quite straight (b).

“The fore legs are quite straight. The bone must be flat from the side, and not round. The foot resembles that of a hare (c), with toes of medium length. On each toe grows a bunch of hair, long and thin (a). The under part of the paw is of an oblong form.

(a) Not so round as the sides of an English greyhound.

(b) Many huntsmen begin to prefer a sloping loin. The reason is that this form was common to the majority of coursing winners in Russia.

(V) Comparison generally used by Russian amateurs. We consider a cat foot a fault for Borzois.

“The hind legs are parallel one to another, slightly set back (not too much).

“The thighs are flat, with very broad bones. The muscles are flat, long, and firm.

“The tail is thin, but strong in its beginning, growing gradually thinner and thinner to the end; it must be elastic, have the form of a sickle, and be of medium length. Its upper part is covered with curly hair, but the hair on the lower part is long and slightly undulated.

“The hair of the dog is curly on the neck, slightly wavy on the back of the dog – as far as the loins – and again more wavy on the thighs, much shorter on the sides, but falls long and satin-like from the chest.

“Personally, we admit as typical colour of the hair only white, grey, yellow, and white spotted with grey and yellow (b).”

In Russia, although judging dogs by points is in vogue, the procedure connected therewith is arranged on different lines to that followed in this country.

(a) Not for dogs in field condition.

(b) All our amateurs were quite astonished when we heard that a black dog (1 think its name was Argos) was proclaimed champion in England; This colour is one of the first proofs of a great deal of Crimean or Caucasian blood.

For instance, forty-five is taken as the complement indicating perfection, and each point of the dog is given five, no particular one having a greater number allowed than another. However, to modify this the various points are placed in order of precedence, according to the Russian standard, they being as follows: Hind legs, fore legs, ribs, back, general symmetry, muzzle, eyes, ears, tail.

In 1892 a Borzoi club was established in Great Britain, and the following is their description of the hound:

Head

Long and lean. The skull flat and narrow; stop not perceptible, and muzzle long and tapering. The head from the forehead to the tip of the nose should be so fine that the shape and direction of the bones and principal veins can be seen clearly; and in profile should appear rather Roman nosed. Bitches should be even narrower in head than dogs. Eyes dark, expressive, almond shaped, and not too far apart. Ears, like those of a greyhound: small, thin, and placed well back on the head, with the tips, when thrown back, almost touching behind the occiput.

Neck

The head should be carried somewhat low, with the neck continuing the line of the back.

Shoulders

Clean, and sloping well back.

Chest

Deep, and somewhat narrow.

Back

Rather bony, and free from any cavity in the spinal column, the arch in the back being more marked in the dog than in the bitch.

Loins

Broad and very powerful, with plenty of muscular development.

Thighs

-Long and well developed, with good second thigh.

Ribs

Slightly sprung at the angle of the ribs; deep, reaching to the elbow, and even lower.

Fore Legs

Lean and straight. Seen from the front they should be narrow, and from the side broad at the shoulders and narrowing gradually down to the foot, the bone appearing flat and not round as in the foxhound.

Hind Legs

The least thing under the body when standing still, not straight and the stifle slightly bent.

Muscles

Well distributed, and highly developed.

Pasterns

Strong.

Feet

Like those of a deerhound, rather long; the toes close together and well arched.

Coat

Long, silky (not woolly), either flat, wavy, or rather curly. On the head, ears, and front legs it should be short and smooth; on the neck, the frill should be profuse and rather curly; on the chest and rest of body, the tail, and hind quarters, it should be long. The tail should be well feathered.

Tail

Long, well feathered, and not gaily carried.

Height

At shoulder of dog, from 28 inches upwards; of bitches, from 26 inches upwards.

Faults

Head, short or thick; too much stop; parti-coloured nose; eyes too wide apart; heavy ears, heavy shoulders; wide chest; “barrel” ribbed; dew claws; elbows turned out, wide behind.

The colour ought to be white, with blue, grey, or fawn markings of different shades, the latter sometimes deep orange coloured, approaching red. Pale brindled marks on the white ground are often found, and are not objectionable, and fawn dogs with or without black muzzles are not unusual. Whole colours are unsatisfactory. The lighter marked animals are the handsomest and the most admired in this country, though, as stated earlier on, one or two heavily coloured dogs of great merit have been shown here.

One Russian admirer of the breed gives some of the characteristics of the Borzoi as follows: “The structure of the body of a pure bred Russian Borzoi astonishes everybody by its thinness, elasticity, and form of the bones. The muscles are not hard and cushion-formed, but on touching, nearly elastic and long-stretched, which enable these dogs to reach any other animal at a short distance with a few leaps. They have a soft, silky, and glossy coat, the hair never hanging down in short hard locks. The character of the dog is mostly morose, but as a pet his intelligence mostly increases, but the most astonishing thing is his sharp-sightedness and rage against other animals when hunting.”

According to our English notion of awarding points I should make those of the Borzoi as follows:

Value.

Head and muzzle ……

15

Ears and eyes………………

10

Neck and chest………

10

Back and loins………

15

Ribs…………………

10

60

Value.

Thighs and hocks……

10

Legs and feet………

10

Stern ……………….

5

Coat…………………

5

General symmetry……………..

10

40

Grand Total, 100.

The height for a dog should be from 27 inches to 31 inches at the shoulder; a bitch about two inches smaller. Weight, a dog, from 751b. to 1051b.; a bitch, from 60lb. to 80lb.

I do not know that measurements are, as a rule, any great guide in determining excellence, still the following figures relating to the well-known Krilutt, and published in the Dog Owner’s Annual for 1892, will give some idea as to what a perfect Borzoi ought to be when analysed statistically in inches: “Length of head, 11½ inches; from occiput to between shoulders, 11½; between shoulders to between hips, 23; between hips to set on of tail, 6¼; length of tail, 21 inches; total length, 73¼ inches. Height at shoulders, 30¼ inches; girth of chest, 33; of narrowest part of “tuck-up,” 22; girth above stifle bend, 13; round stifle, 11½; round hock joint, 6½; below that joint, 4½; round elbow joint, 8¼; above that point, 8¾; girth, midway between elbow and pastern, 6½; round neck, 17; girth of head round occiput, 16½; girth between occiput and eyes, 16½; girth round the eyes, 13¾; and girth of the muzzle between eyes and nose, 9 inches. Weight about 981b.

As to the above, Captain Graham tells me he measured Krilutt carefully on more than one occasion, but could not make him more than 29¾ inches at the shoulders, and I have made his full height bare 30 inches.

It may be said that I have not entered with sufficient fulness into the history of the Borzoi, as he is known in Russia, and given the names of the various strains some writers claim there are in his native country. We are, however, contented with the animal as we have him here, and to tell his admirers that there is a strain of the hound, known as the Tchistopsovoy Borzoi, another as the Psovoy Borzoi, that the Courland Borzoi is extinct, and other such matter, would be a little too confusing.

And really so much has appeared about this dog since his popularisation in this country that is of doubtful truth, care ought to be taken in what is reproduced.

One recent writer tells us that, even so far back as 1800, certain Borzoi of the Courland strain were sold for from 7,000 to 10,000 roubles apiece, which, in our money, cannot be computed at less than from 1000 l. to 1500 l. a head! No wonder that so valuable a hound has become extinct (on the principle that the best always die), and it is interesting to learn that, at a time when we in England were giving 50/. each or little more for our very best hounds, more than twenty times that sum was being paid in Russia for similar quadrupeds.

Still the Borzoi always did flourish in the dominions of the Czar, and the Imperial kennels at St. Petersburg usually contain from fifty to sixty full grown Borzois and almost as many puppies. There are fourteen men kept to look after and to train them to their proper work, and the nature of this I have already stated. Whatever may be urged to the contrary, it must further be said that, in pace and general excellence for hare coursing purposes, this Russian hound is far behind our own good greyhound; but, as already stated, it is not our admiration for him as a sporting dog which has made him fashionable. His shape and elegance have made his fortune here, nor, so far as the present outlook is concerned, is it likely to wane in the near future. Perhaps before this volume is in the hands of the public a special exhibition of Borzoi will have taken place, for arrangements for holding one at South-port, Lancashire, are in progress, and it will be under the auspices of the Borzoi Club. Her Grace the Duchess of Newcastle has consented to judge, and, no doubt, the novelty of a canine exhibition of the kind will ensure its success, especially as it will be the first occasion upon which a lady of such social distinction and noble family has officiated in the judging ring.

Year of Event:

Country:

Personal Collections:

Source:

Author:

Dogs:

Persons: